Waterscape Park

Waterscape Park

Waterscape Park

PROJECT STATEMENT

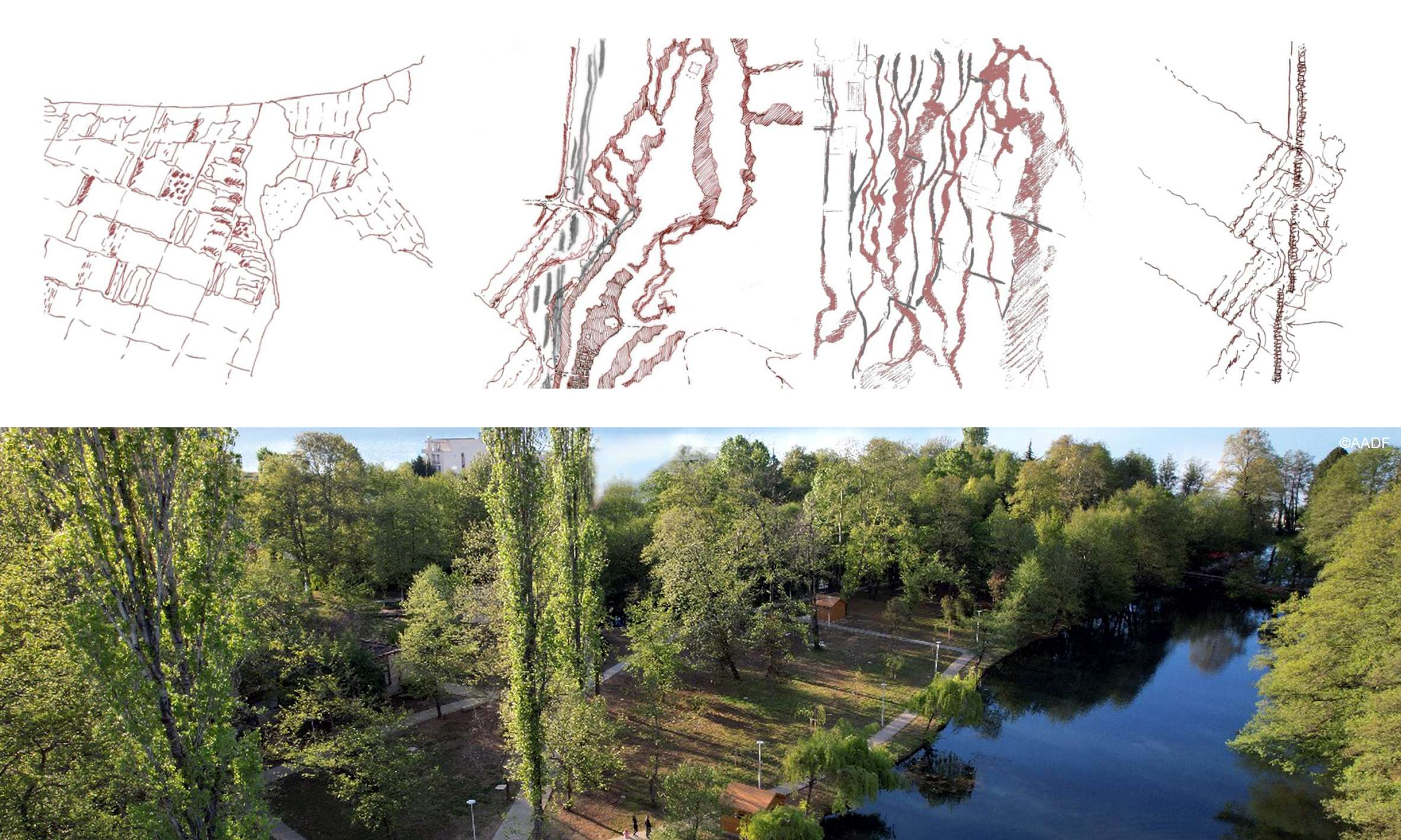

Drilon Park is the first phase of a broader intervention spanning the area between the springs, waterfront, and the village of Tushemisht. Starting from Drilon Park, the project initiates a comprehensive landscape and urban regeneration that transforms a historically enclosed site into a vibrant public space. Located between Lakes Ohrid and Prespa — a region of exceptional ecological and cultural value — the project redefines the relationship between nature, water, and community. It adopts a systemic approach, viewing the park as part of a connected network of topography and hydrology rather than an isolated green space. Serving as a model for sustainable tourism, the design carefully balances human use with landscape preservation, ensuring ecological and cultural integrity for future generations. Water remains central — not only as a scenic element but as vital ecological infrastructure and a catalyst for social and spatial renewal.

PROJECT NARRATIVE

Background

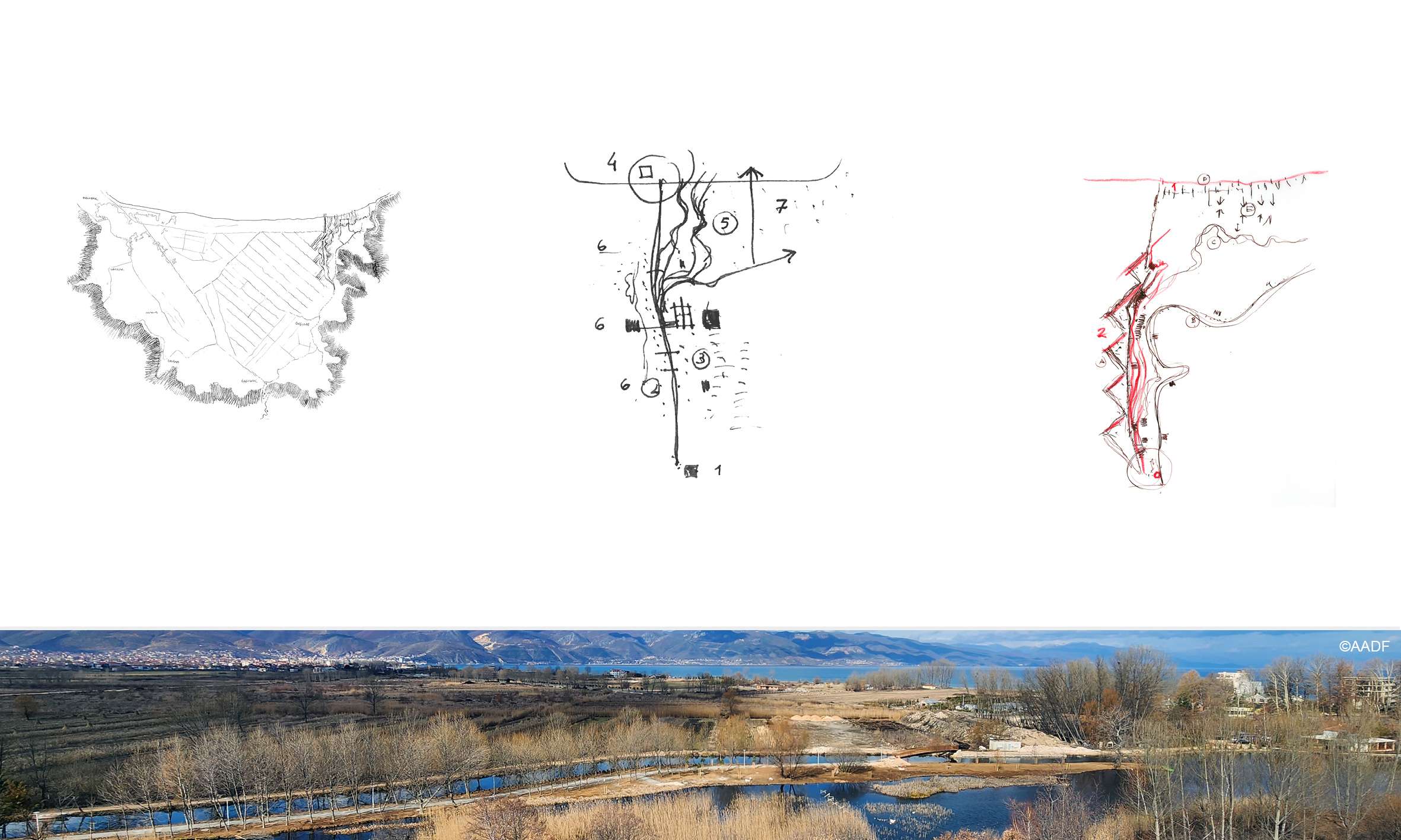

The project site is located in a landscape of remarkable amplitude and continuity, where agricultural fields, mountainous horizons, and a meandering river converge into a lake as vast as the sea. Historically, the park was part of a private estate — the former residence of Prime Minister Enver Hoxha — and later included in a national park framework. Despite its official designation, the area remained environmentally degraded and disconnected from public life.

The park is deeply embedded within a broader system of water-dependent landscapes: lakes, rivers, wetlands, and springs that shape the identity and environmental value of the region. This ecological richness, however, was underutilized and compromised by fragmented planning, mismanagement, and limited public access.

Issues of the Site

Several challenges informed the design:

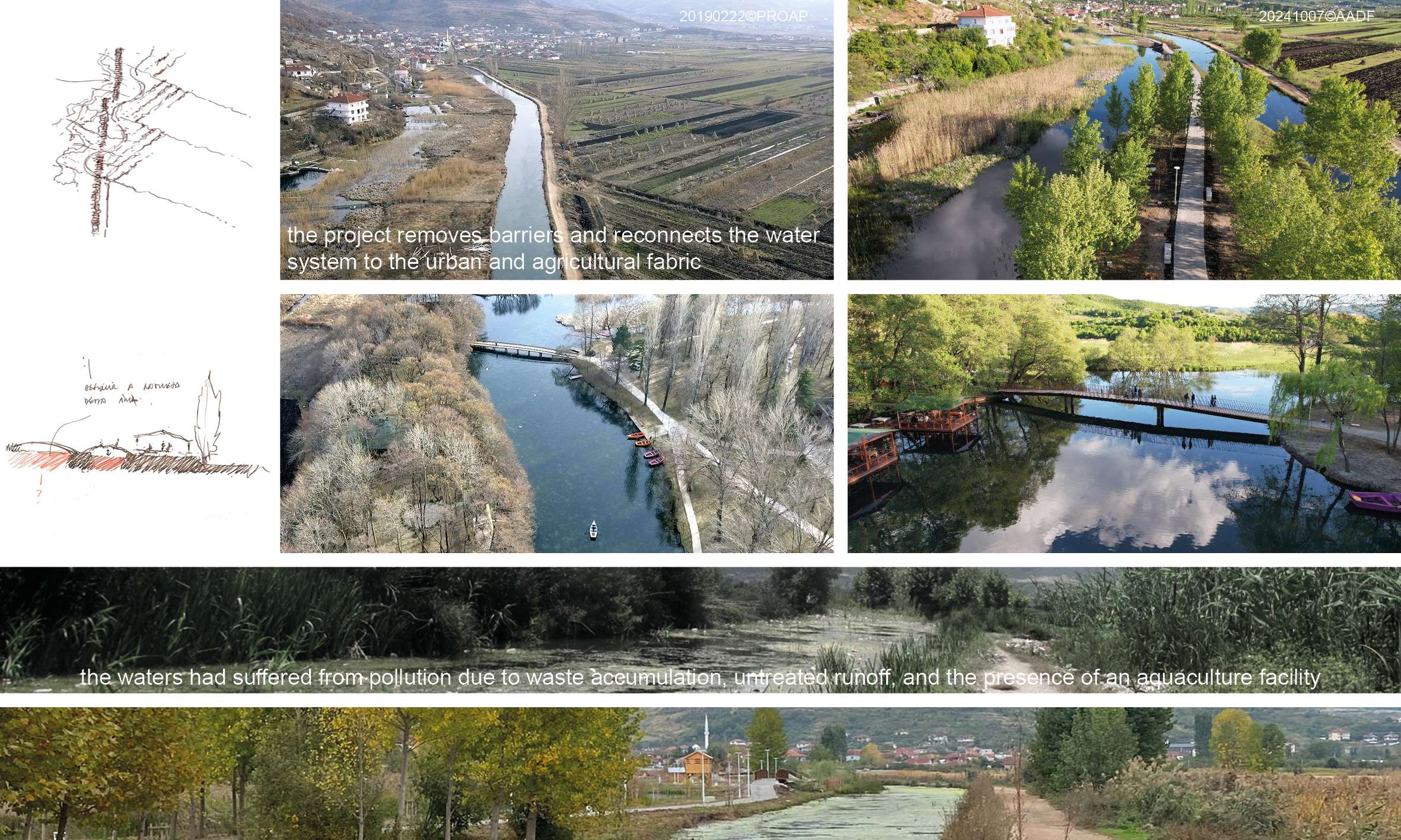

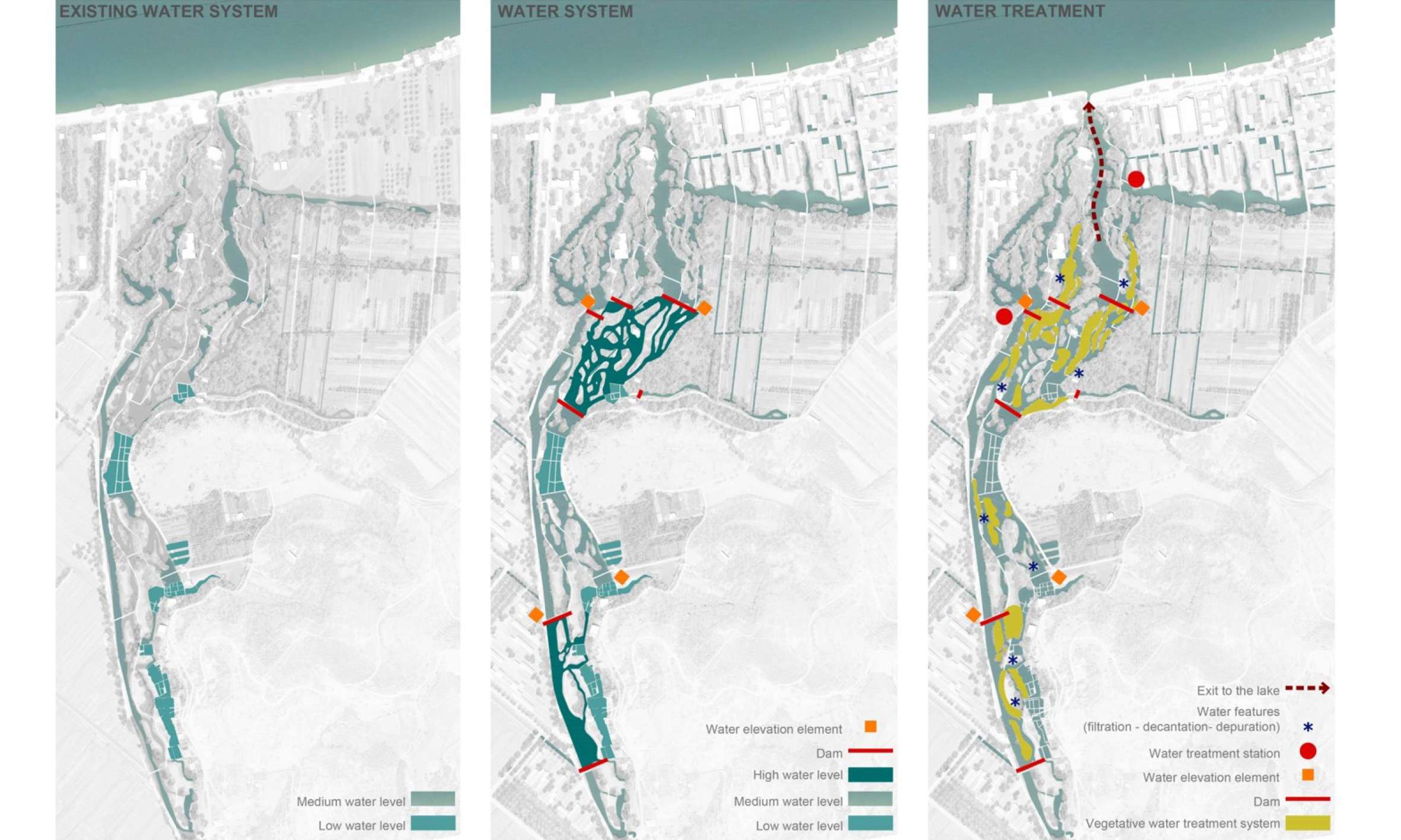

- Environmental Degradation: The Drilon springs, once a symbol of natural purity, had suffered from pollution due to waste accumulation, untreated runoff, and the presence of an aquaculture facility. This compromised water quality and the ecological integrity of the park.

- Disconnection: A major issue was the disconnection between the lake and its surrounding landscapes, both natural and urban. The road infrastructure created a hard barrier between water and land, preventing natural flow and human access.

- Underutilization: Despite its scenic and ecological potential, the park lacked an integrated system for public use. Paths, access points, and programmatic functions were sporadic or absent, reducing its social and recreational value.

- Fragmented Identity: The presence of historical structures, mature tree plantings, and spontaneous pathways had created a layered but disjointed landscape. Without a unifying vision, the site’s historical and environmental richness remained underappreciated and at risk.

Approach

The design response proposes a waterscape as a celebration of the void, a spatial and ecological reimagination of the site’s core elements. The strategy reframes the park as a permeable, open system — much like the river basin it belongs to — and integrates natural, built, and social components into a cohesive whole.

- Reconnecting Water and Land: By rerouting the existing road and offsetting the park boundaries, the project removes barriers and reconnects the water system to the urban and agricultural fabric. A new spatial arrangement introduces mixed-use areas, where buildings blend with gardens, canals, and green infrastructure.

- Water-Centric Design: Water is not treated as a backdrop but as the protagonist. A network of navigable canals, springs, and catchment systems brings water to the center of public life. This system also functions ecologically, supporting biodiversity and improving drainage and water quality.

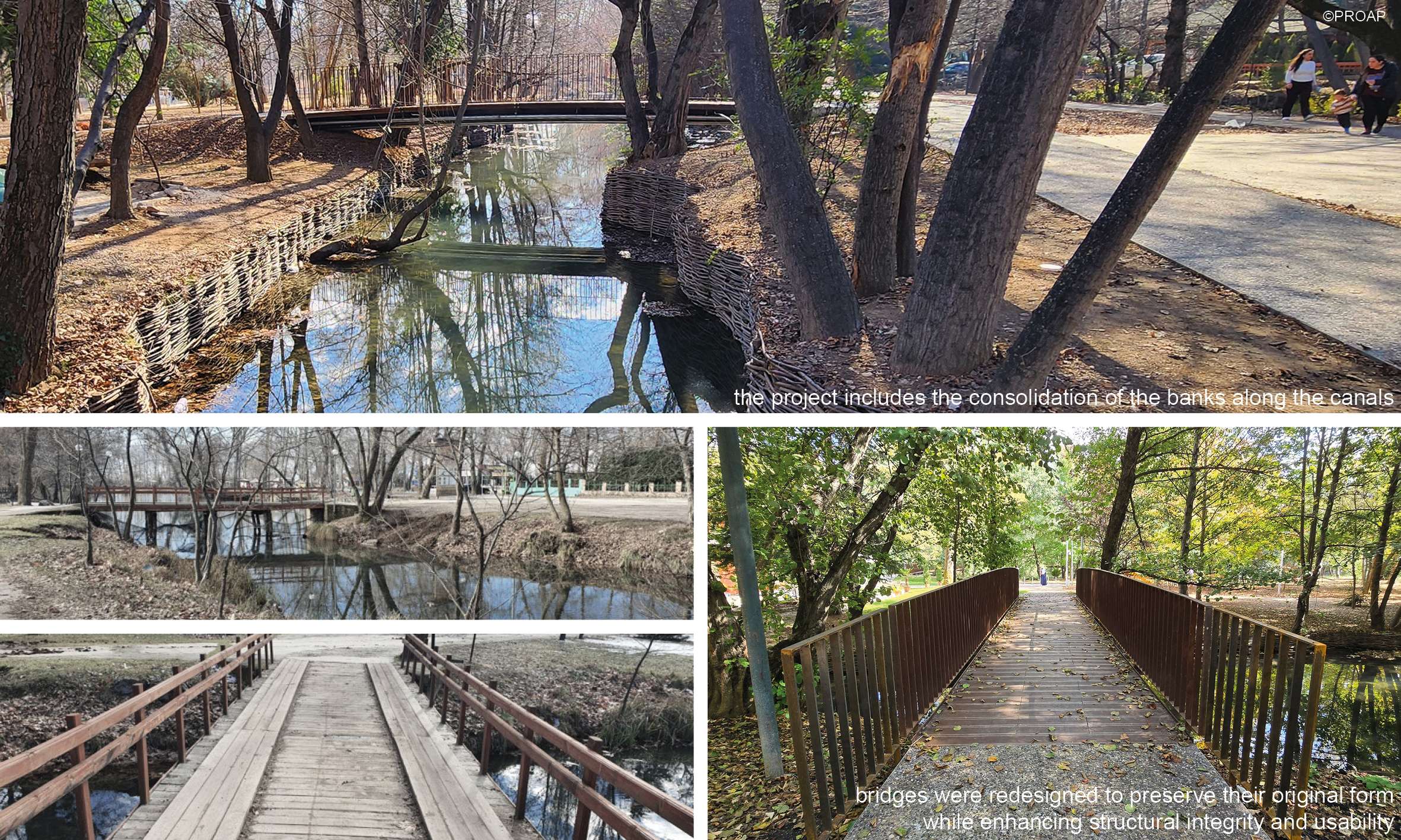

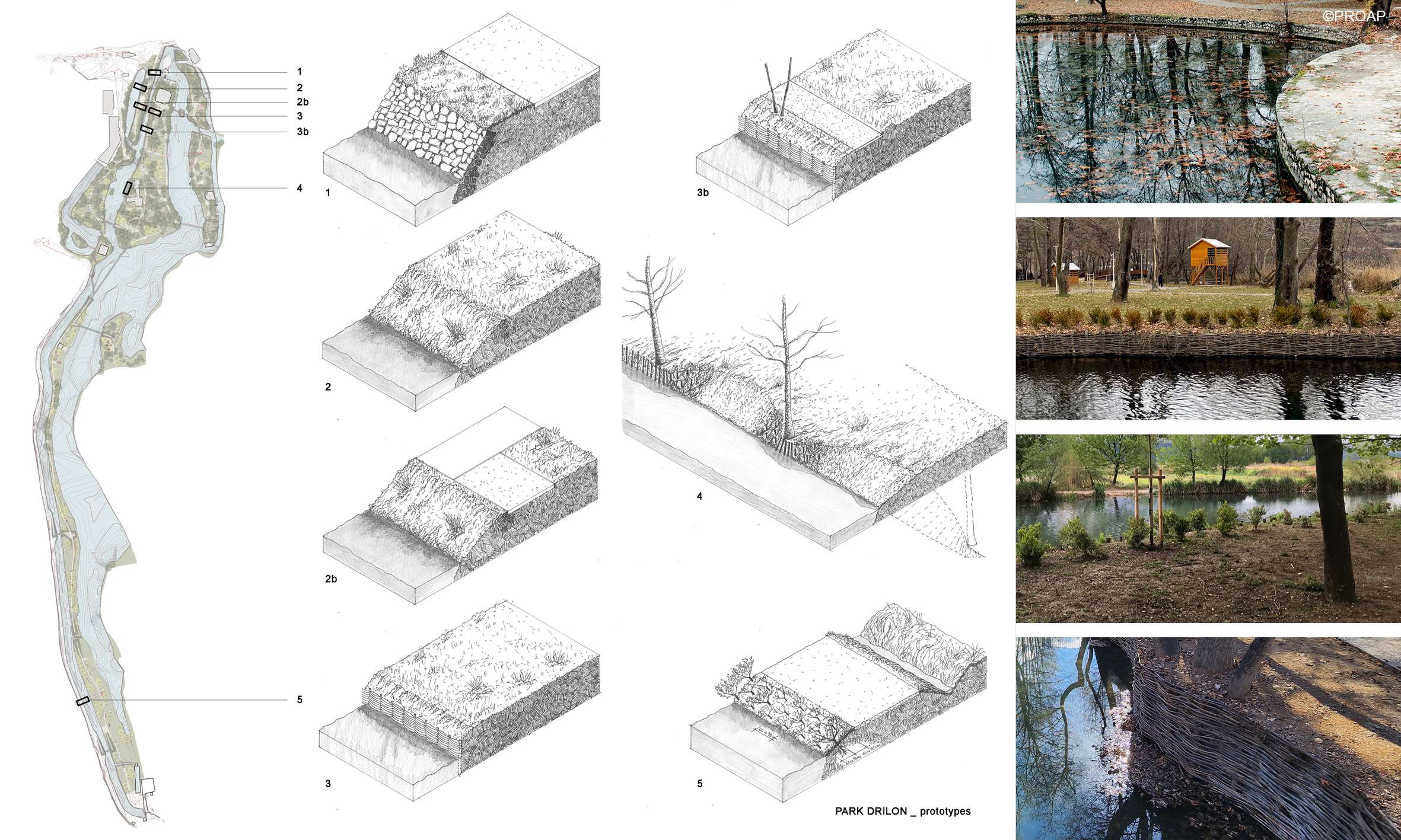

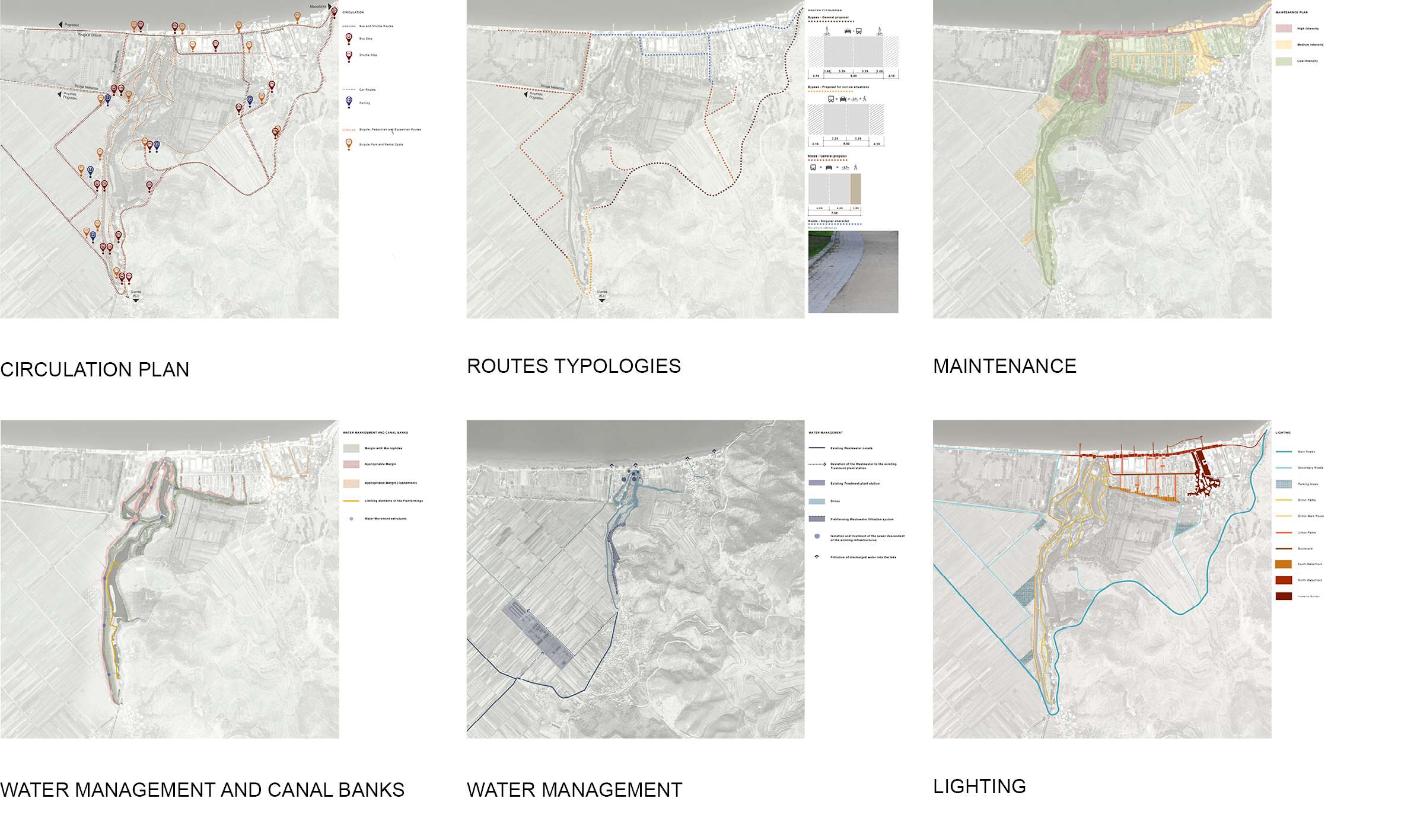

- Consolidating Riverbanks and Lake Margins: To ensure long-term ecological stability and prevent erosion, the project includes the consolidation of the banks along the canals. Using soft engineering and naturalistic techniques, these interventions reinforce the edges while preserving the visual and ecological continuity of the landscape.

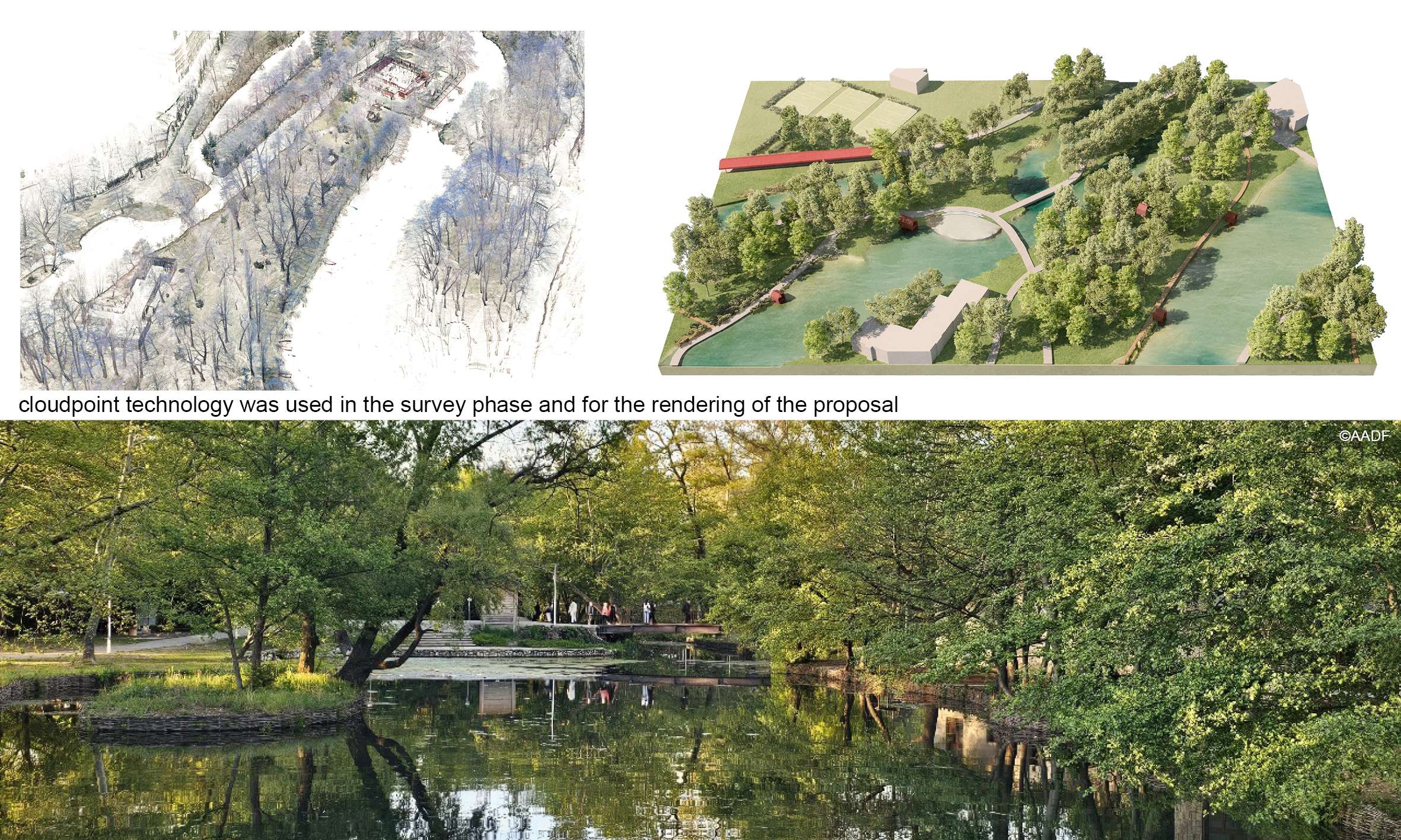

- Preserving and Enhancing Vegetation: The existing park included mature trees from the 1950s–60s, which were carefully preserved. New plantings were introduced with sensitivity, reinforcing the park’s character and ensuring long-term ecological stability.

- Architecture and Interpretation: New architectural elements — including an interpretive center, pavilions and bridges — were designed in dialogue with the existing buildings of notable architectural quality. Materials and forms were chosen to create harmony and continuity.

- User-Centered Circulation: Instead of imposing rigid paths, the design builds on existing user behavior, enhancing informal routes and connections. A continuous pedestrian and bicycle network encourages slow mobility and offers varied experiences of the park — discovery, rest, interaction. The project also revitalizes the traditional use of rowboats, offering an alternative, low-impact way to explore the park’s water system. This approach extends the experience beyond Drilon Park to the surrounding area, reinforcing connections with the broader landscape and nearby communities

- Inclusive Design: The project recognizes that a public park is foremost a space for people. Its design reflects the needs of diverse age groups, cultural backgrounds, and lifestyles. Program elements include plazas, gardens, walkways, and leisure areas that support both individual reflection and community gathering.

- Sustainability and Maintenance: The design promotes sustainability through passive systems and minimal interventions. Soft infrastructure — like green filtration zones and permeable surfaces — reduces the need for high-maintenance equipment.

ASSESSMENT

This park demonstrates how a low-budget, ecologically sensitive intervention can generate meaningful transformation. By leveraging the site’s unique history, mature vegetation, and water infrastructure, the design creates a unified, accessible, and resilient public space. It shifts the paradigm of development from exploitation to restoration — creating a new model for tourism and everyday life that respects landscape systems and secures them for future generations.

TEAM:

OBRAS Architectes

MetaSoft360 (Yra Ipi)

Class Construction

ARK

CLIENT:

The Albanian-American Development Foundation (AADF) is dedicated to supporting Albania’s path towards sustainable development. AADF was founded as a non-profit entity in 2009, with support from USAID and the U.S. government. AADF is committed to a people-centered approach, understanding that meaningful partnerships are the foundation of successful development. AADF works closely with local communities, experts, government bodies, and international organizations to build a shared vision and co-create long-lasting solutions.