'Bustani ya Taamuli' (Garden of Contemplation) - Tabora Hermitage Garden

For this project, we were granted the rare opportunity of designing a spiritually informed garden for a hermit. A place which, in-line with his daily meditative practice, could provide moments of reflection, whilst also supporting his isolated lifestyle, allowing him to exist as part of self-sustaining landscape. An accompaniment to his modest dwelling, the garden simultaneously becomes an extension and dissolution of the self, simply a network of life.

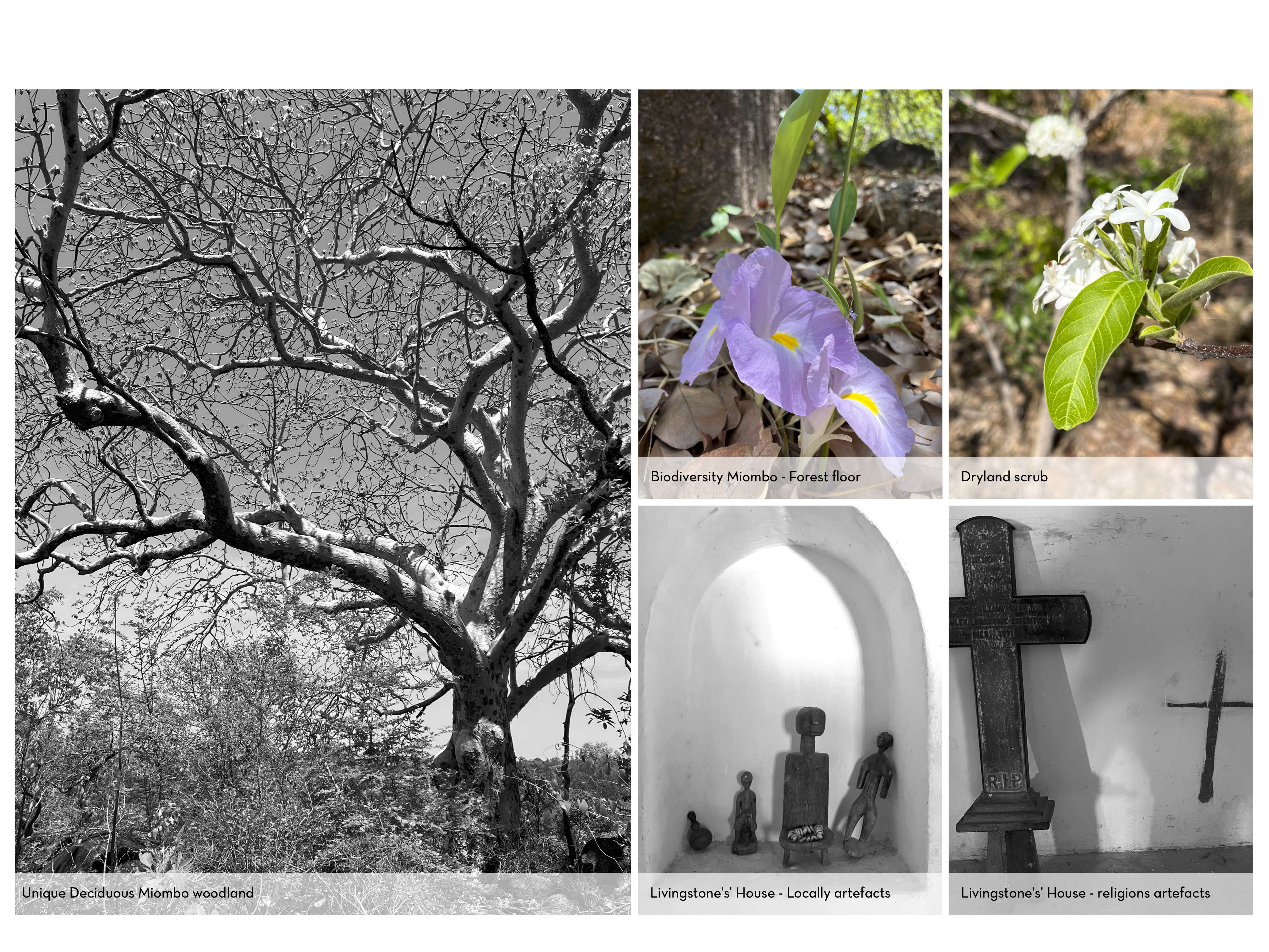

Derived from eremos, Greek for wilderness, the etymology of the word ‘hermit’ is perhaps the most succinct way of demonstrating the importance of landscape in the practice of eremitism. Living in solitude, often in the sanctity of nature, follow- ing a monastic practice of self-discipline and prayer, religious hermits are thought to have existed since the fourth century. Isolated in the deserts of Egypt, following his political and ecclesial exile, St Anthony the Great is believed to have pioneered the eremitic tradition. Although found globally, the hermitages of East Africa remain some of the most notable. In Ethiopia, what is left of the old growth forest, is almost entirely that which is has been protected by the church. Existing as part of the nat- ural landscape, the lifestyle fosters a mindful, compassionate approach to all that is living. It is no coincidence that before becoming a hermit, our client’s career similarly focused on the protection of wildlife. Recognising the holiness of the forest environment, our design utilises the architecture of sacred spaces to nest the garden’s most spiritual points within interwoven, concentric circles formed by the layering of simple murram paths and re-wilded spaces.

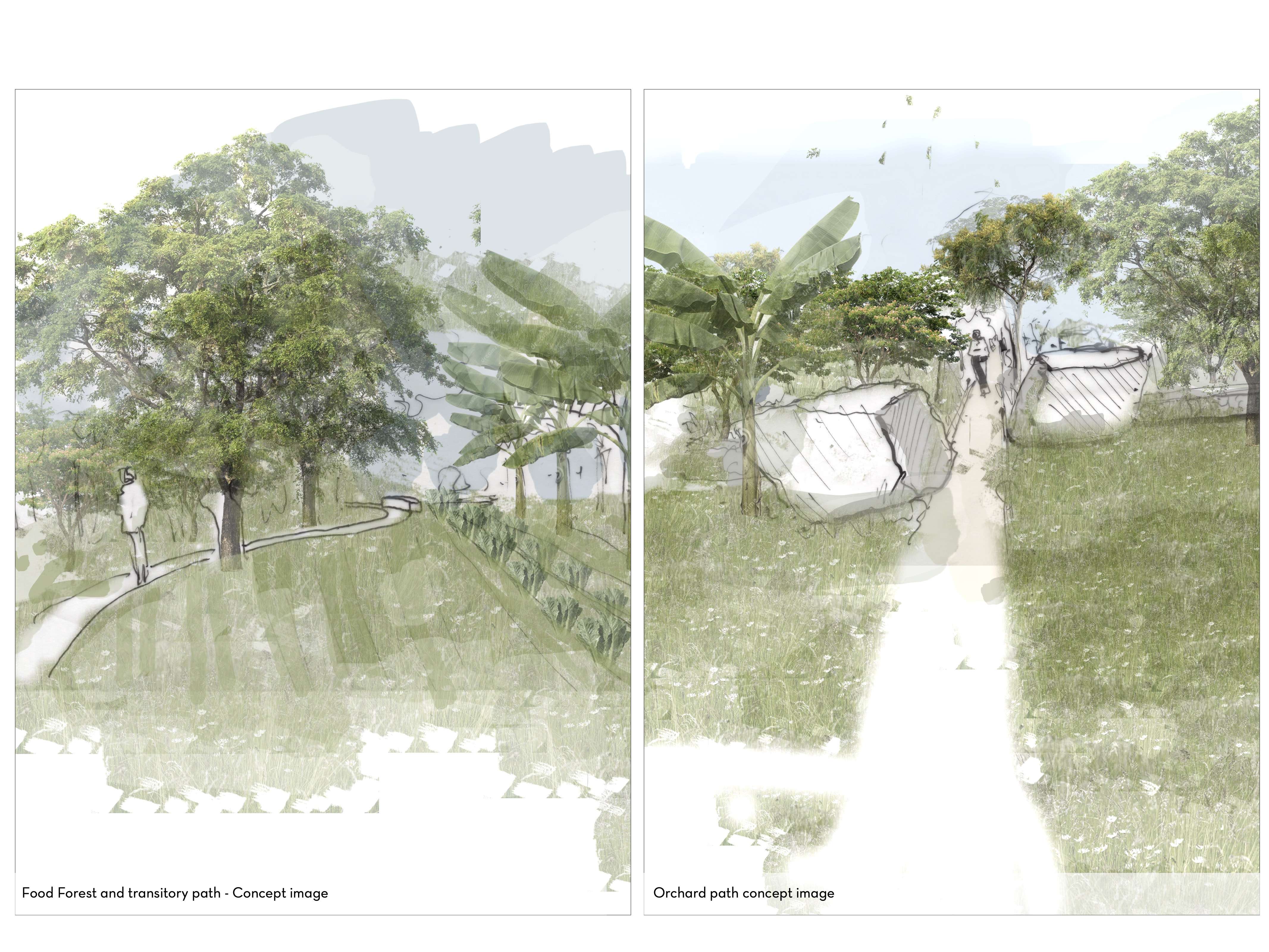

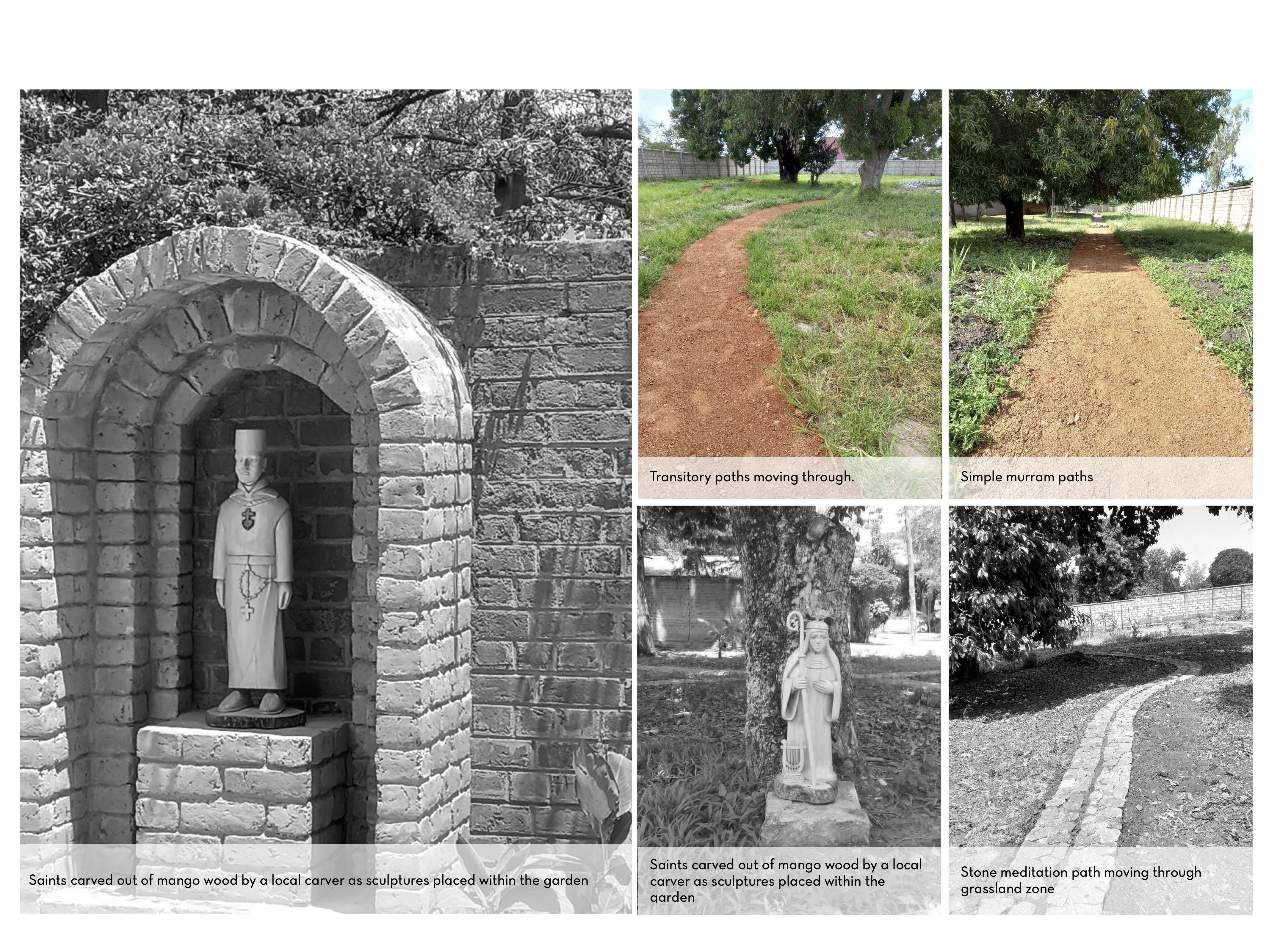

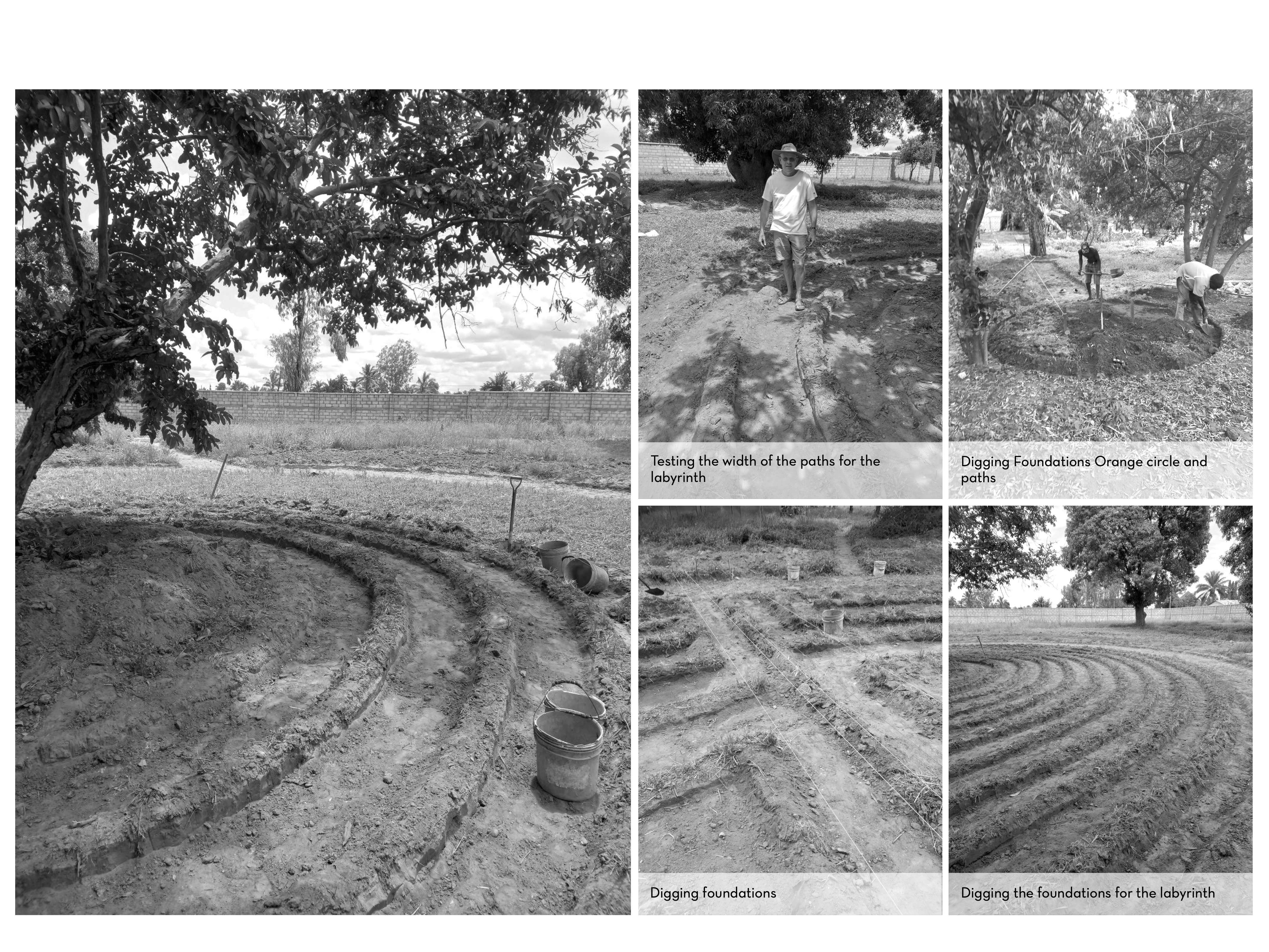

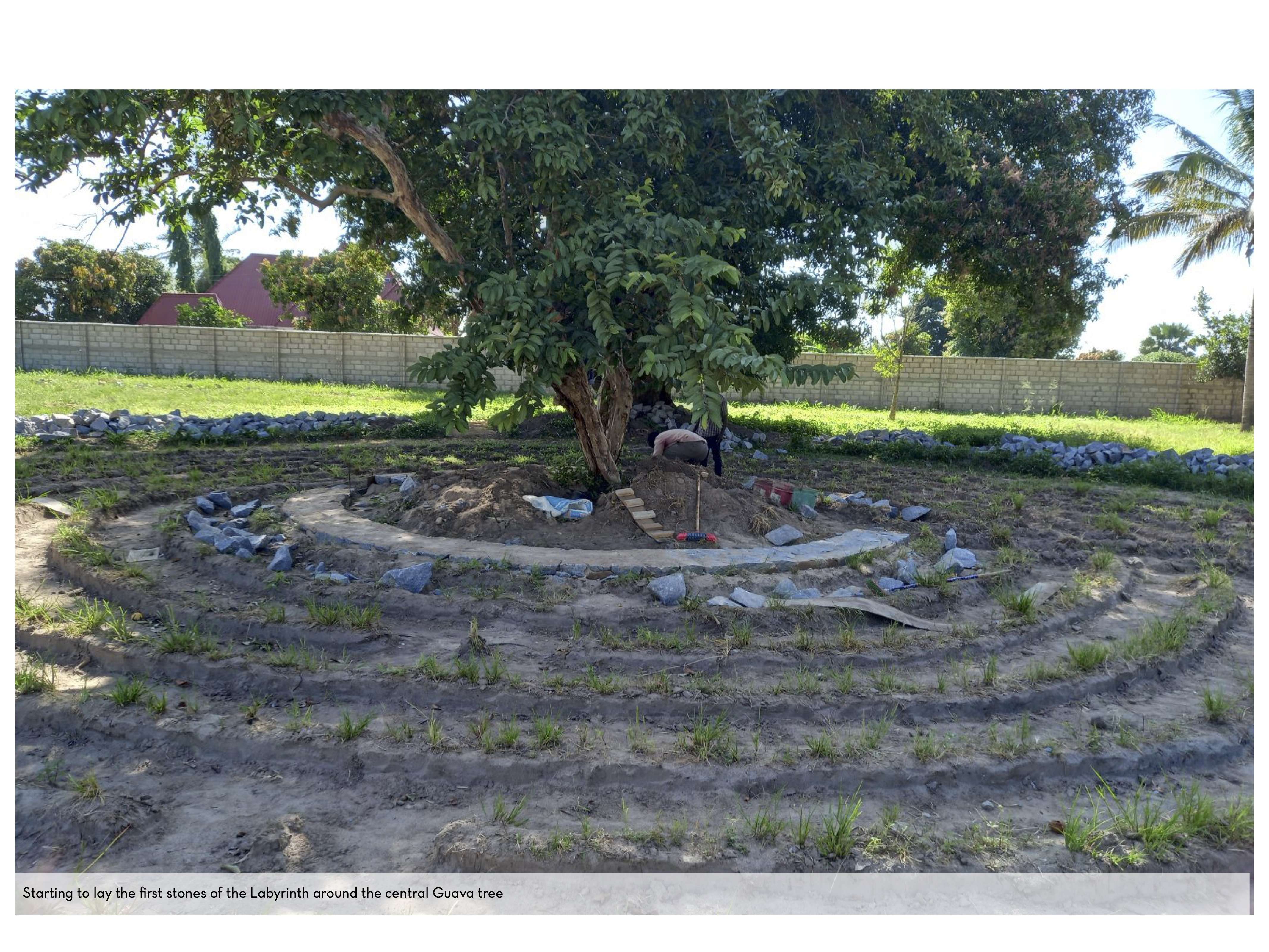

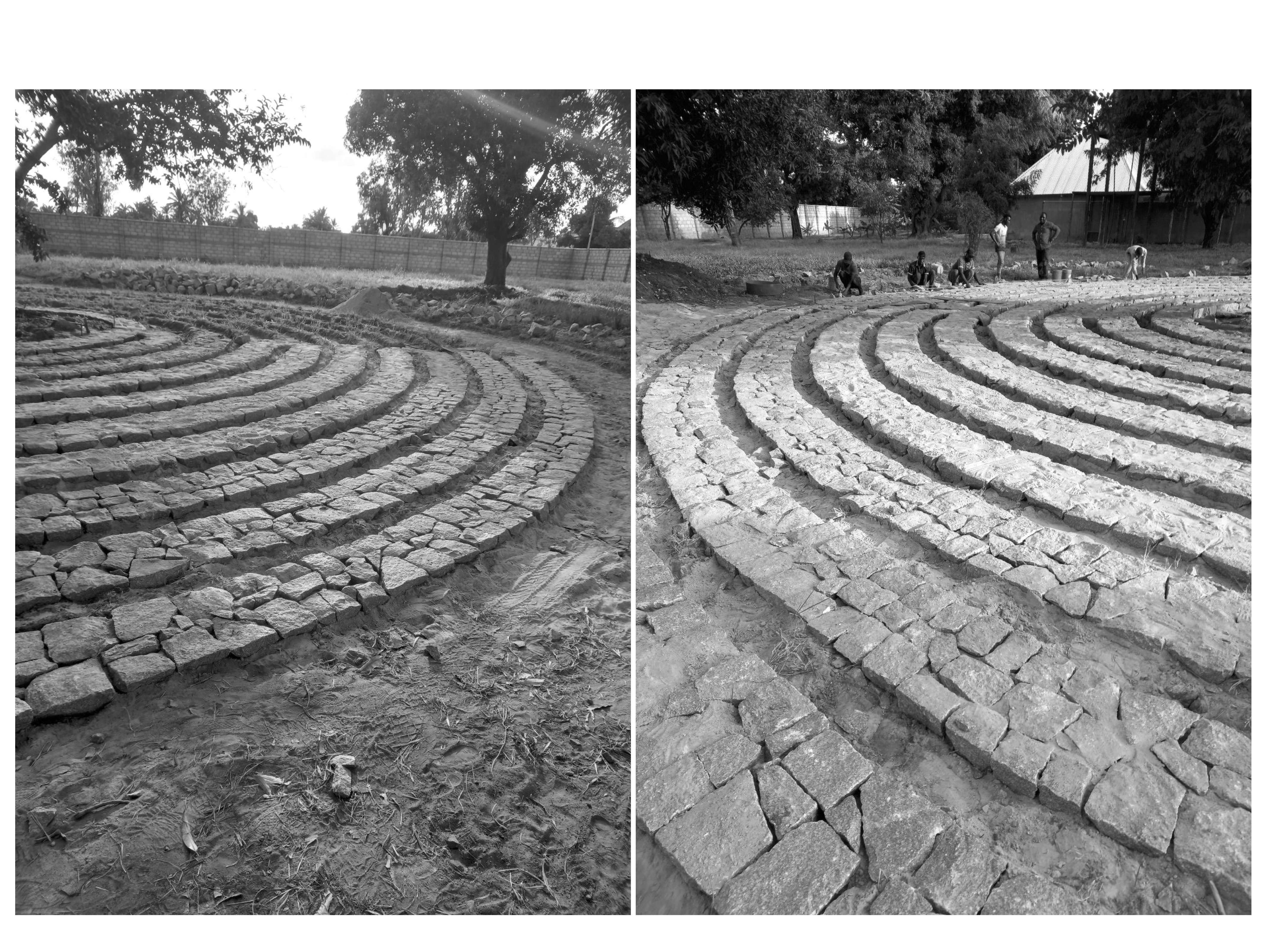

Our design process began with a focus on the hermit’s daily practice of which meditation, specifically walking meditation play a central part. To embody this flow-like movement, we wanted to create explorative and revelatory experiences via poetic combinations of transitional spaces and destinations. From straight granite paths and meandering walkways softened by growth, to open terraces and shad- ed groves, each emotive feature sculpts the walking journey. Paying attention to catholic tradition, in reference to the Way of the Cross the garden is structured around a series of paths and points of reflection, the final point being a guava tree, located at the centre of the labyrinth. The labyrinth on-site is constructed entirely by hand using the local granite, a technique and style that pays specific homage to the cobblestone labyrinth built by pilgrims to Chartes in France during the Medieval Period. From the first known example of a Christian Labyrinth, inlaid on the floor of St. Basilica of Reparatus in Algeria around 324 AD, devoted individuals like monks have utilised their structure as a tool for quiet contemplation. With their brain-like folds, labyrinths architecturally visualise the challenging process of discovery one undergoes while practising meditation. The point around which the labyrinth and consequentially the surrounding garden is built, the guava tree stands as the rooted centre.

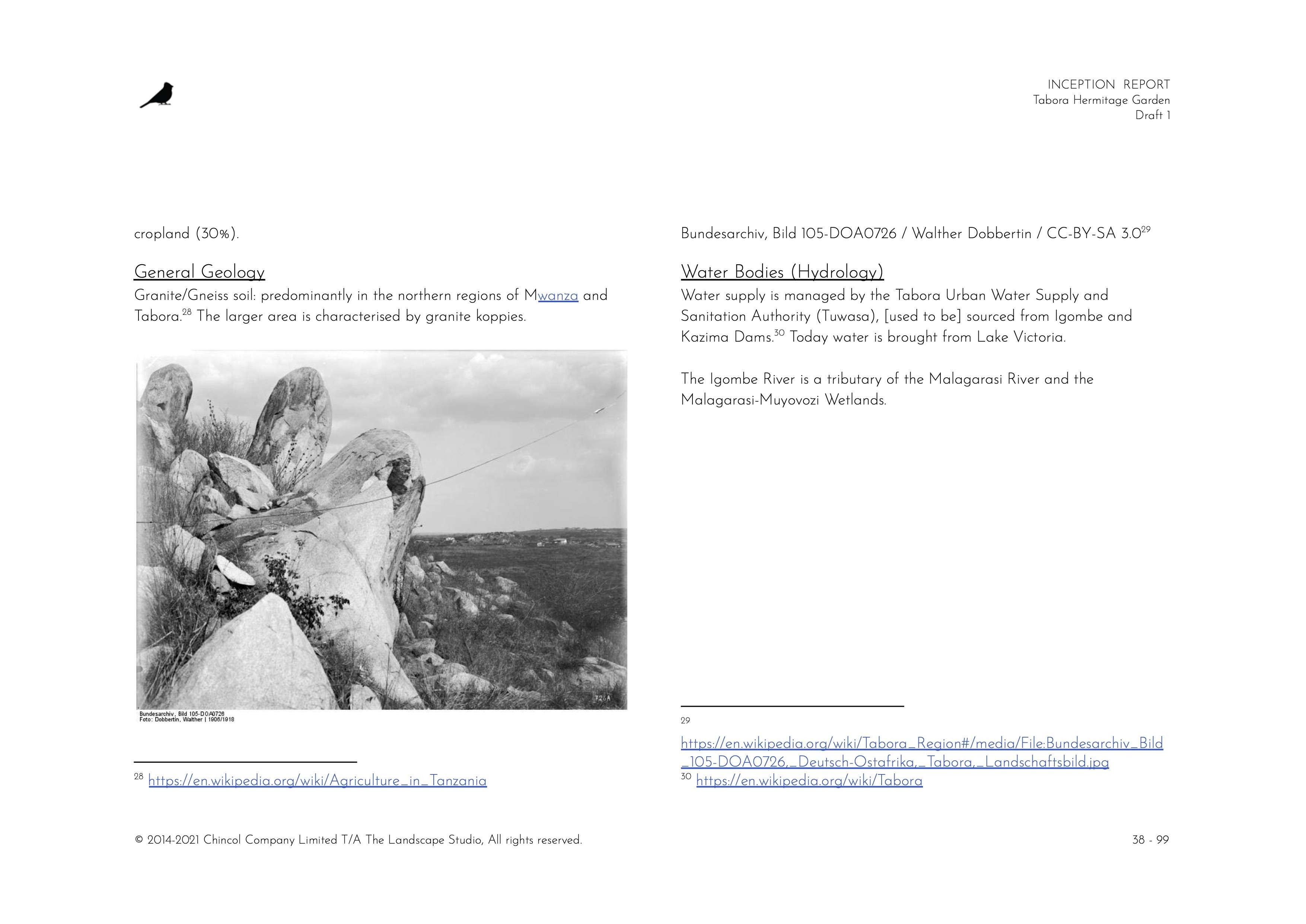

In order to understand the landscape, at the start of the project, we spent considerable time in Tabora. Whilst travelling around the area, everywhere we went, we noticed the presence of granite. The stone, mostly found in crushed form, was often left discarded: heaped up in corners across the site and on the side of the road; or used as if it were rubble: piled up as hardcore or mixed with cement to be processed into uniform building blocks. Such treatment of this precious material, highlighted to us a likely abundance in the region and so we went searching for the source. This type of thorough inquiry has become an important part of our process. Not only does it allow us to source local materials that, tried-and-tested, work symbiotically with the landscape, but it also provides access to important kinds of materials that would otherwise be hard to find in such remote parts of the world. As it turns out, the Tabora region is almost entirely underlain by granite, the mountainous landscape recognisable for its jagged rocky outcrops or ‘koppies’. After some investigation, we visited a dry dusty site, a landscape scattered with colossal granite boulders. Some of the rocks remained untouched, surfacing organically from the dirt, whilst others had become disfigured and fragmented in order to be broken down into rubble. Although the site was technically a quarry, that title implies the presence of some kind of industry, rather than the informal activity that occurs here. The people here have engineered a simple method for cracking apart granite boulders. Strategically positioned upon wooden stilts, small fires are lit on existent fissures or points of weakness. Subject to heat and water thrown on the stones when hot, the cracks dilate to the point of breaking, with more stubborn fractures needing to be pried apart with a crowbar. Across the site the crackling of small fires would, every so often, give way to the sonorous splitting of these giants. As with many of our projects which rely on the skills, energy and knowledge of native people in order to materialise for the Hermitage Garden, we collaborated with locals on-site to work the granite harvested in Tabora. The calming addition of this tactile stone amongst the vibrant vegetation generates natural accents with a grounding presence. Frequently used as a method of wayfinding, to create paths, walls and the labyrinth, the granite functions as a connective thread, becoming a literal and metaphoric bedrock that facilitates a fluid yet anchored journey.

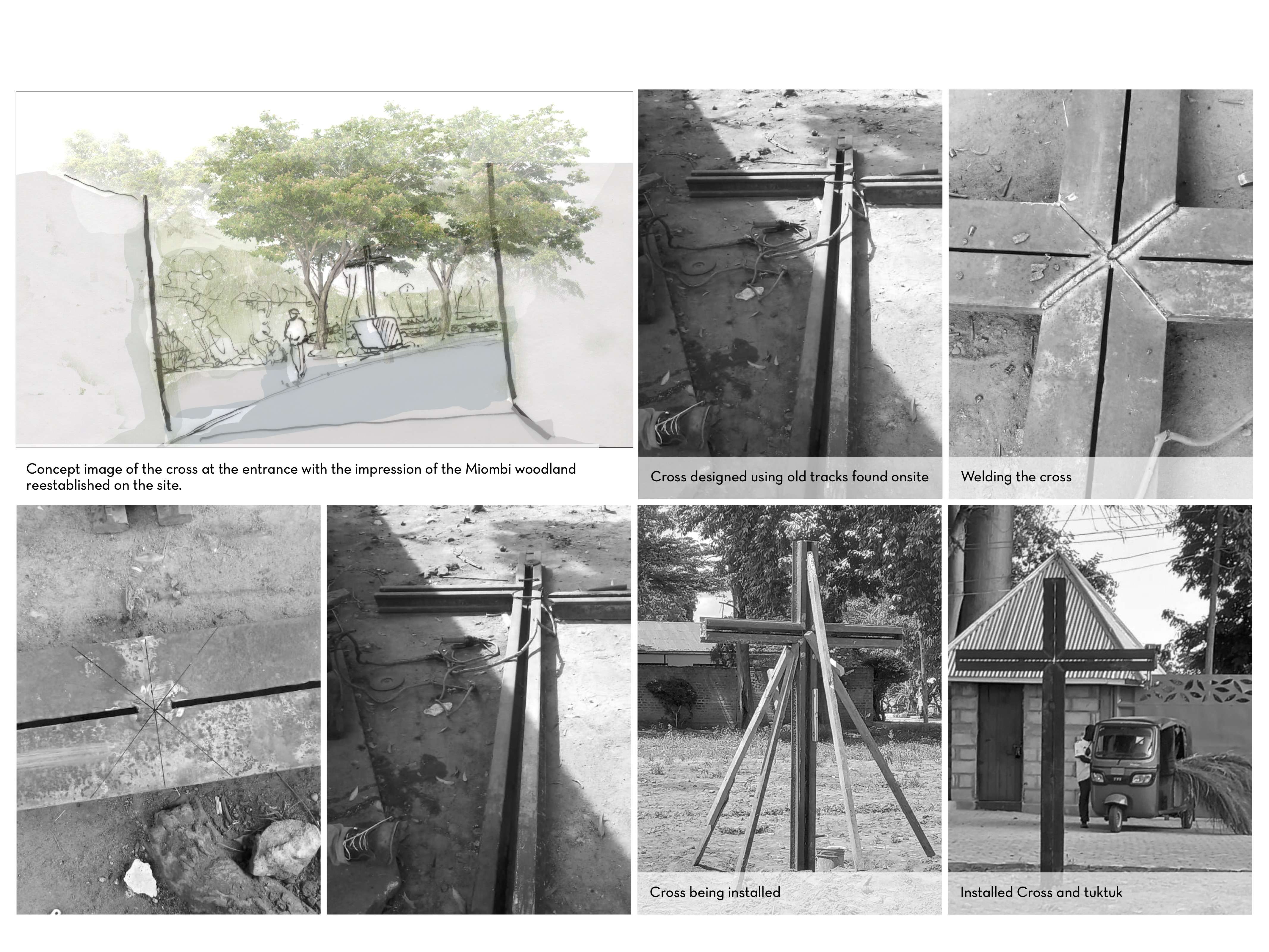

Whilst exploring the site we also unearthed some metal railroad tracks. It quickly became clear to us the painful past such tracks signified. As you walk around Tabora, its streets lined by mango trees whose expansive trunks have grown over two meters wide—the ancient history of this small, rural town is apparent. Located in the heart of Tanzania, the town is the traditional centre for the Nyamwezi Tribe, known for their identity as long-distance traders. However, taking sinister advantage of Tabora’s central location between Africa’s trading routes, during the nineteenth century, the town rapidly developed into a key post on The Central Slave and Ivory Trade Route. In order to acknowledge and memorialise the tragic history of the site we decided to repurpose the railroad tracks to construct a metal cross. Marked by time, the steel material, now weathered to the deep earthy colour of rust, brings into being the tex- ture of history. Located at the entrance, the metal cross stands as a thoughtful emblem that can be carried throughout one’s meditative exploration of the garden.

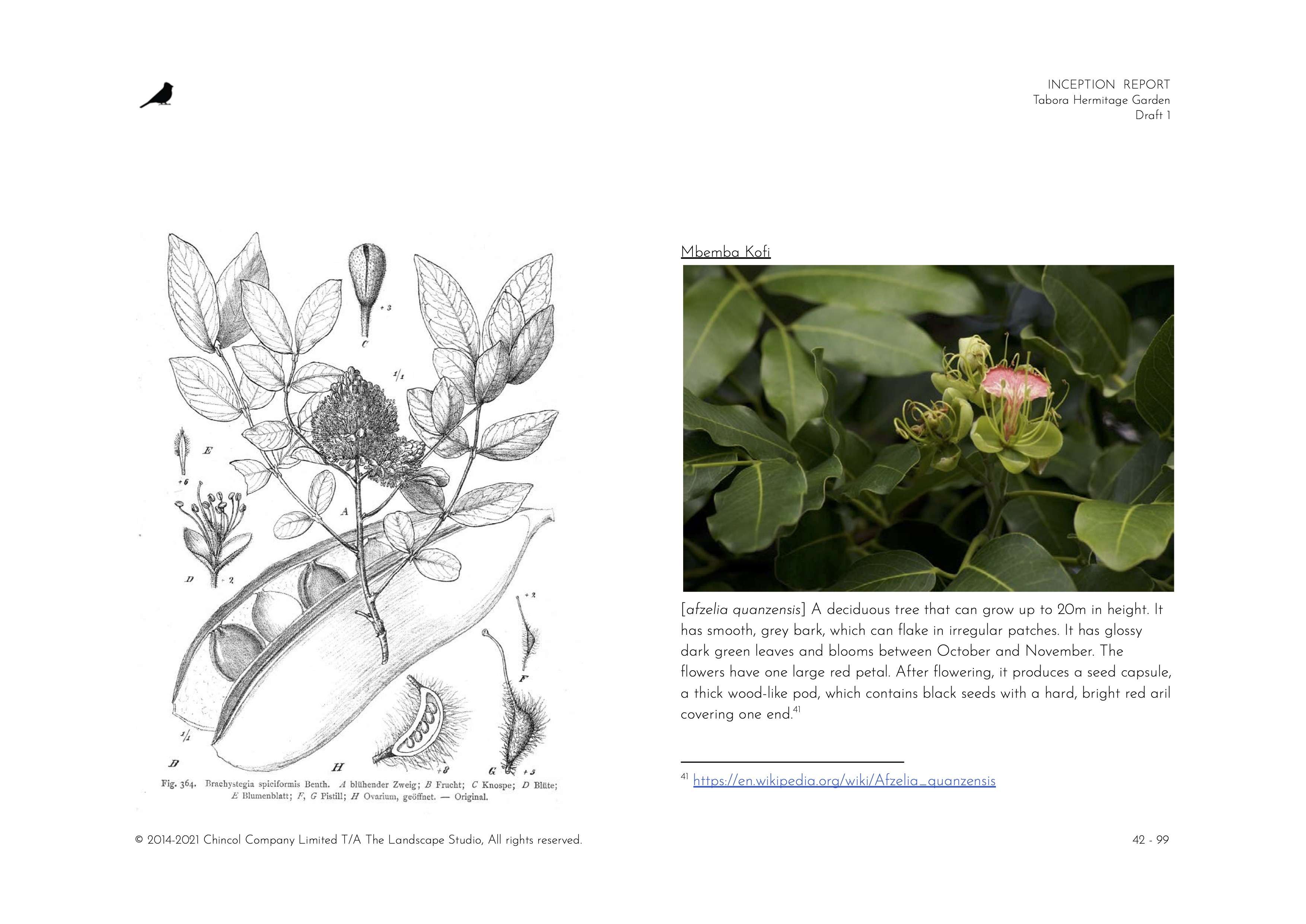

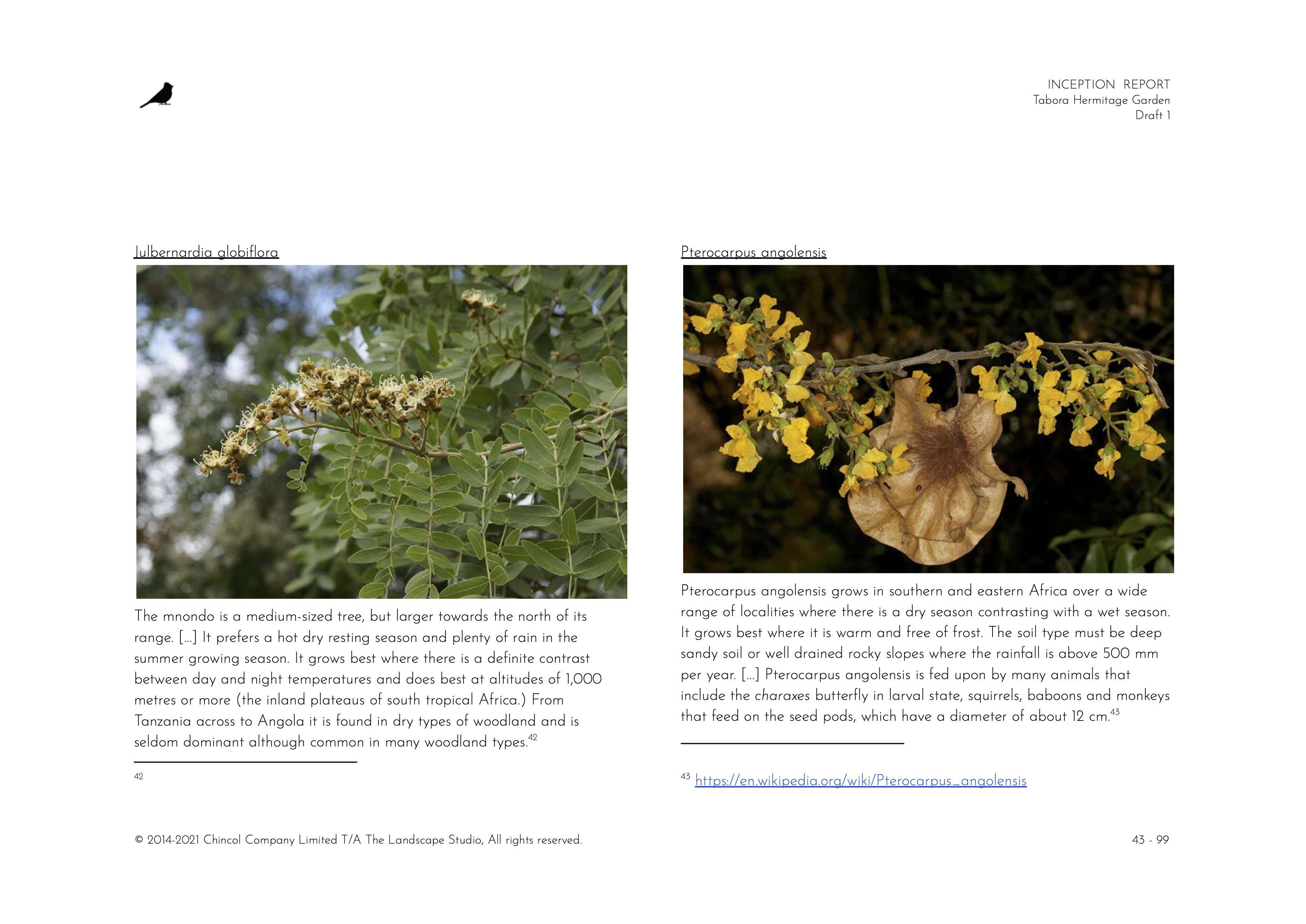

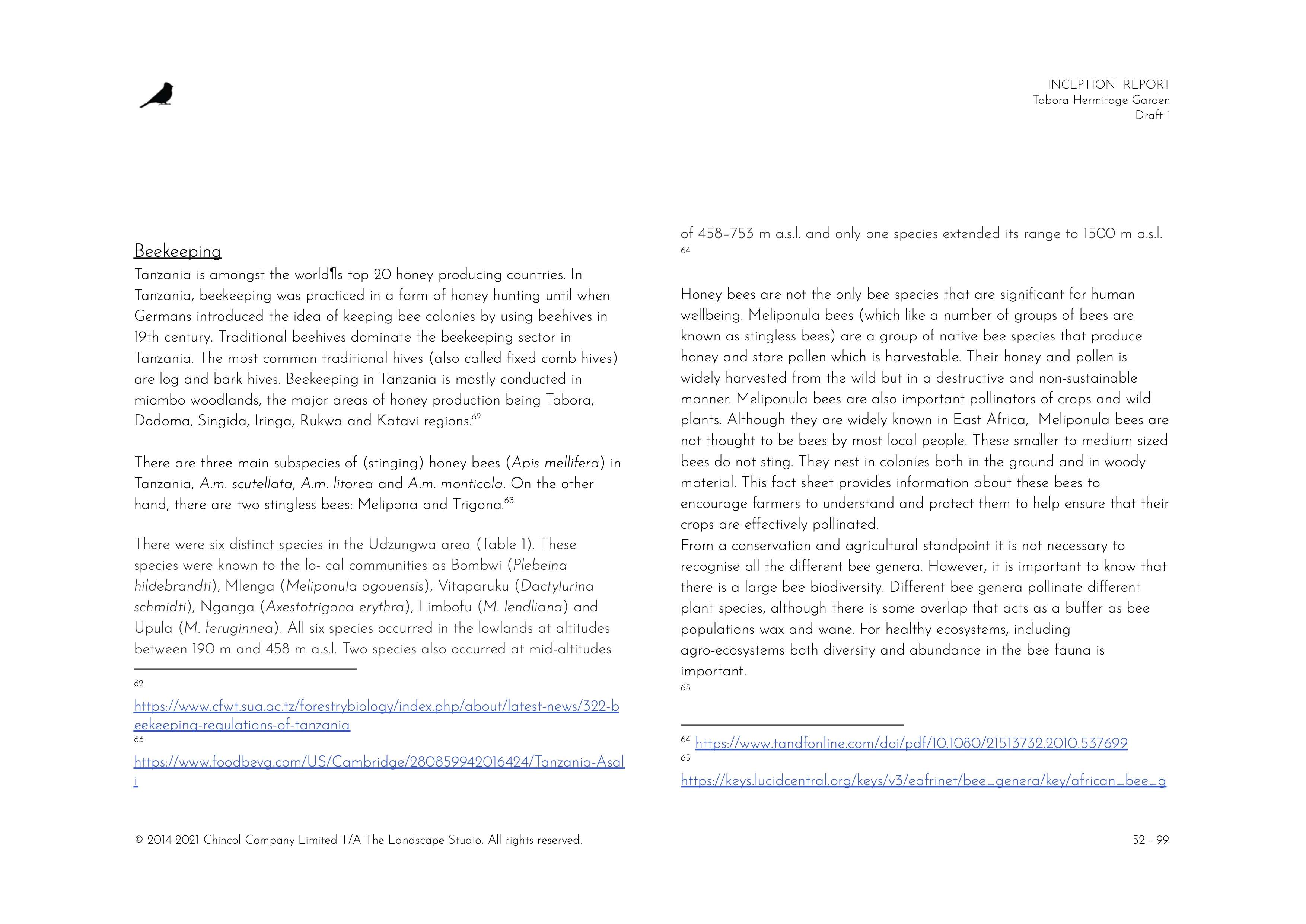

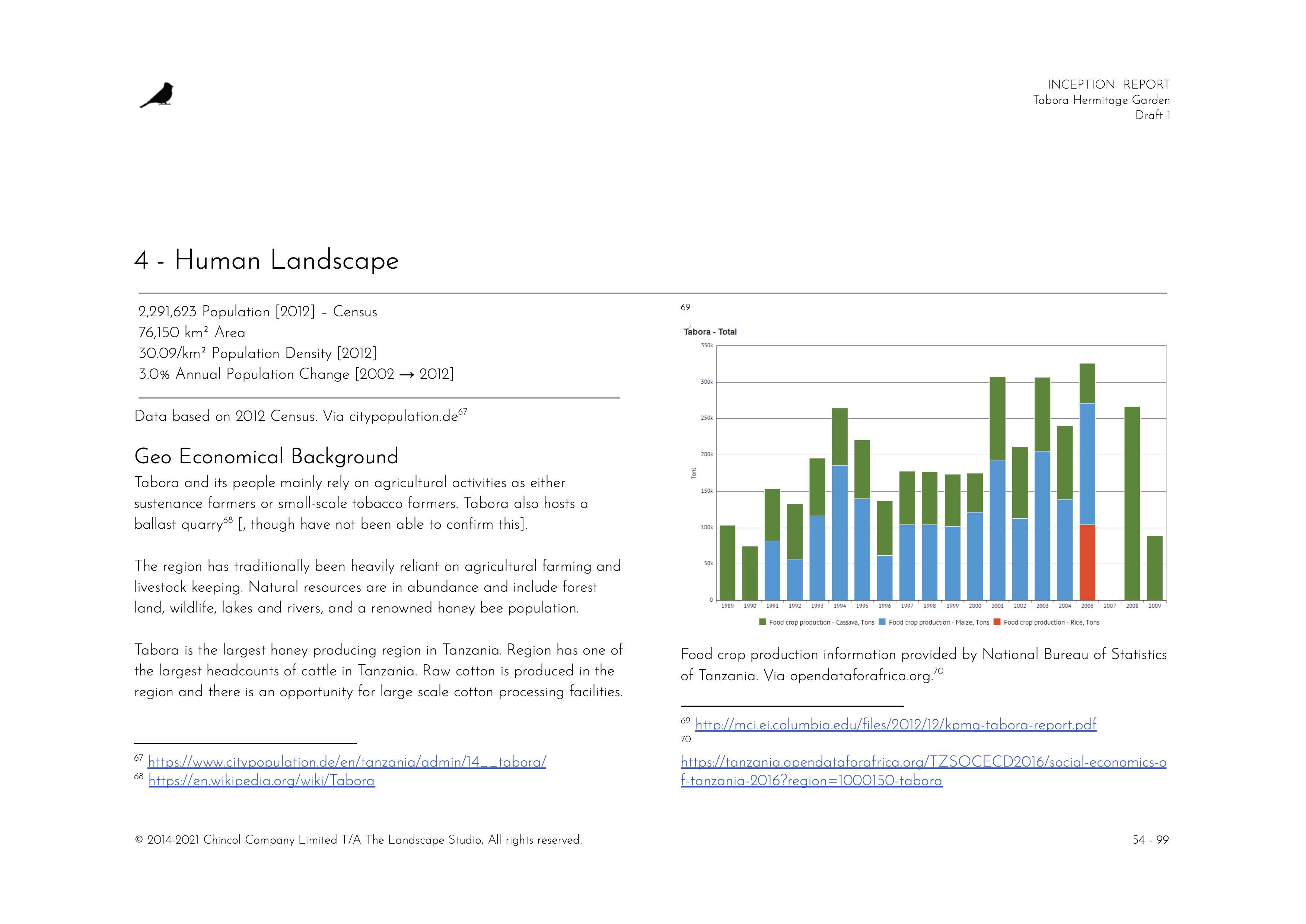

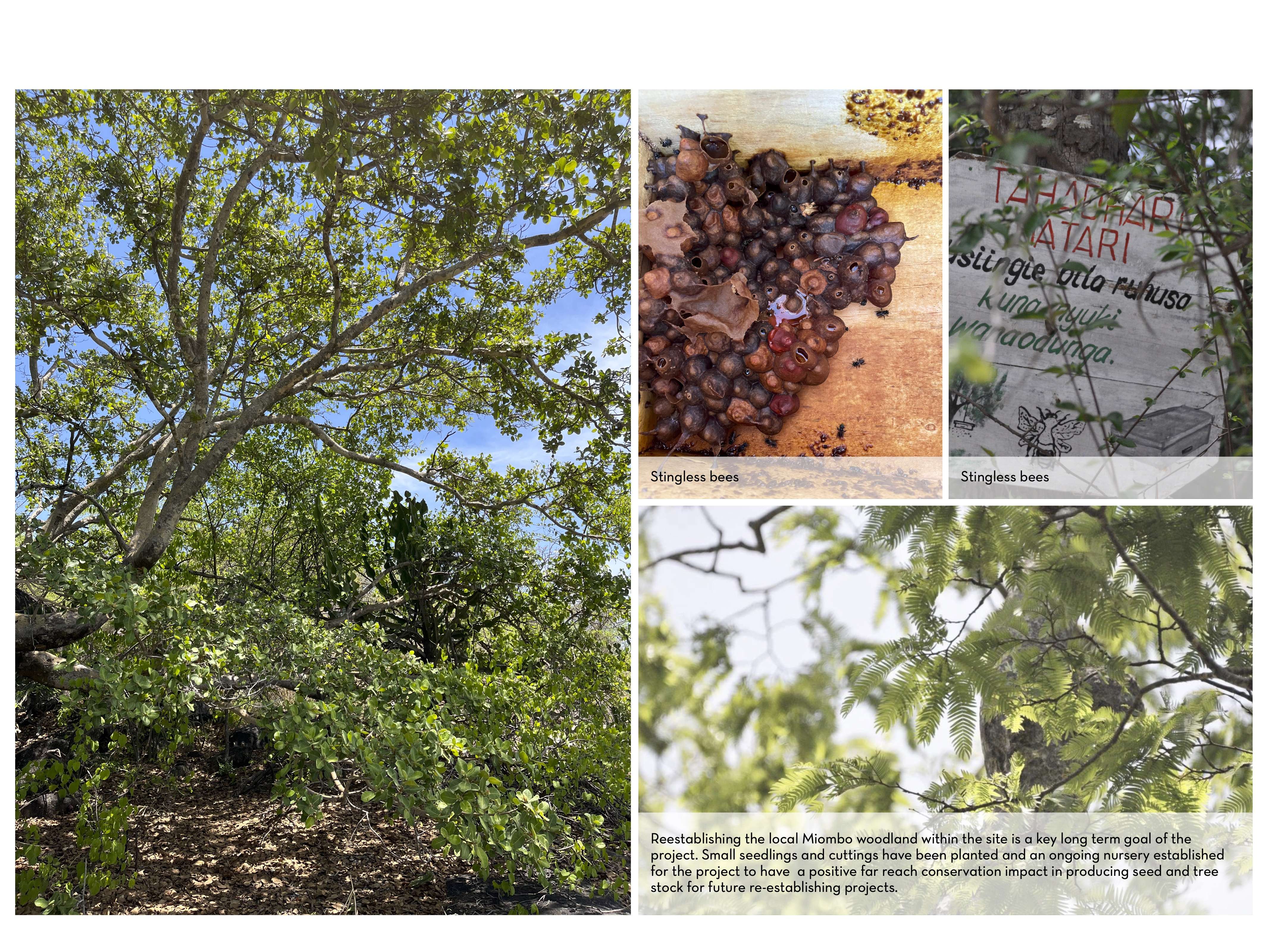

Another characteristic of Tabora is the Miombo woodland, which forms a horizontal belt spanning from Angola in the east to Tanzania in the west. ‘Mi- ombo’ is the Swahili word for Brachystegia, a genus of tree comprising a large number of species that make up the woodland. Throughout the ecoregion, the majority of old-growth Miombo woodland and hence the biodiversity it contains has been destroyed. Areas are often cleared for the production of charcoal, commonly seen around major roads and urban centres, or to produce staple and cash crops like maize, cassava and tobacco. Re-culti- vating a biodiverse woodland on-site will, by proximity, assist recovery of wildlife in the surrounding areas. Placing the welfare of the woodland at the centre of our design, the garden seeks to embrace the seasonal changes between the wet and dry seasons.

As implied by their title, isolation is an integral part of a hermit’s religious practice. With this in mind, generating a productive garden became a central element of the project brief. However, given the plethora of issues certain forms of agriculture promote namely a lack of biodiversity through the propagation of monocultures, and the various knock on effects, depreciation of soil nutrients, increased risk of diseases and so on we decided to cultivate a food forest. Unlike conventional agriculture, food forests are a sustainable method of farming in which the diversify cacophony of species that comprise the intricate layers of a forest are sustained, whilst simultaneously supporting the production of consumable ‘crops’. The site, located in a tropical savanna climate, is therefore suitable for supporting a variety of non-invasive ‘farmable’ species including coconuts, cashews, guavas and bananas. Alongside the more obvious forms of nourishment available, the gentle care this garden requires, speaks to a more expansive philosophy, the collective power of subtle actions and their ability to bear fruit.

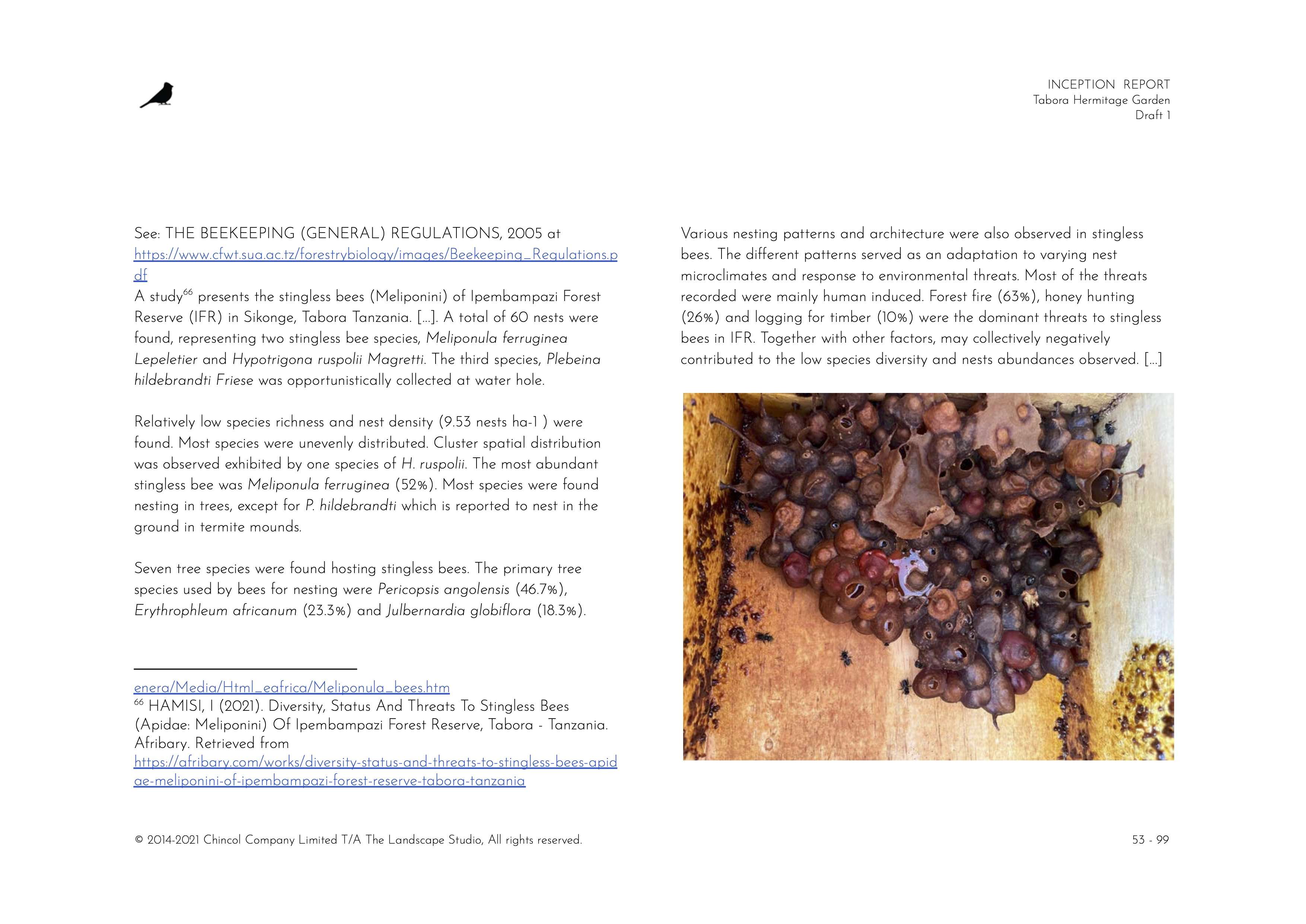

As pollinators, the native meliponines, a genus generally termed ‘stingless bees’are essential for pollinating the various parts of the hermitage garden, such as the food forest. The three different species present in Tanzania specifically aid the regional Miombo woodlands, with each one re- sponsible for pollinating a select variety of crops and wild plants. Like conventional stinging bees, meliponines produce honey and pollen, both of which are harvestable. Scientifically recognised for possessing more antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that their stinging counterparts, the honey from these bees has become highly sought after in luxury markets like beauty, wellness and fine-dining. However, without the protection of their sting, they are more vulnerable to opportun- istic animals like vultures and poaching by humans who, when harvesting their produce in the wild destructively cut down entire indigenous trees in order to access nests. The working and nesting habits of these bees is similarly fragile. Building their nests inside cavernous spaces hollowed out sections of trees, termite mounds, or the wall-cavities in old buildings, for instance—hives appear as bubble-like structures in which young are cocooned or honey is stored.

With the view to conserving and protecting these bees, we initially planned to incorporate some method of beekeeping. Yet, since the inception of the project, a colony of meliponines have nested in a disused water tower on-site. Following nature’s own design, we will be leaving the water tower undisturbed. An integral member of this microcosmic forest community, the return of these bees to the garden exemplifies how when we are listening many species, even ones as fragile as the sting- less bee, are happy to exist alongside us. Rewilding is always exponential, meliponines being one of them.

The long term beauty lies in the slow process of re-establishing the rare miombo woodland which is the local vegetation within the region. This process of rewilding the site around the network of meditation paths will take many years to establish. We are looking a a time frame of 10-20 years for the planted project to reach maturity. In essence our presentation of this project is to reflect on the process of the design and implementation which has been slowed down to embrace the slow regeneration of the unique local ecology and biome.

Similarly to the slow progression of the re-wilding, our input in the project has from the initial time onsite to understand the location and unique qualities been led by the 'hermit' way of life. Father Patrick has inched the project along with our guidance and so the photos we share are of ones shared quietly by him to us at various intervals. Now the paths have been built the project grows and changes in silence and in contemplation in Tabora. We hope one day to be able to return and photograph the changes in the garden as nature finds her space, but until that moment our communication with Father Patrick is that of silence and wonder.