Landscape of care: an The Alzheimer Garden in Rome

Objective of the Proposal

The project proposes the creation of a therapeutic, sensorial garden specifically designed for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. It seeks to establish a welcoming and stimulating outdoor space that enhances quality of life through interaction with nature, sensory engagement, and active participation.

General Objectives

-

To improve the overall quality of life for people with Alzheimer’s by offering a calm, engaging, and multisensory environment.

-

To support physical and emotional well-being through contact with plants, soil, and seasonal rhythms.

-

To create a relaxing atmosphere that helps reduce anxiety and stress associated with the condition.

-

To encourage active involvement in simple horticultural and creative activities that support residual motor and cognitive abilities.

Social Objectives

-

To promote social interaction among participants through shared gardening tasks and collective care for the space.

-

To foster the exchange of stories and experiences in a context that values presence over performance.

-

To create an inclusive setting where caregivers, family members, staff, and guests can interact outside of clinical routines.

Environmental Objectives

-

To implement sustainable gardening practices such as organic cultivation techniques, composting, and resource-conscious maintenance.

-

To increase biodiversity through the use of native plants and the creation of microhabitats for insects and small animals.

-

To raise ecological awareness among participants and the wider community, reinforcing the connection between environmental stewardship and personal health.

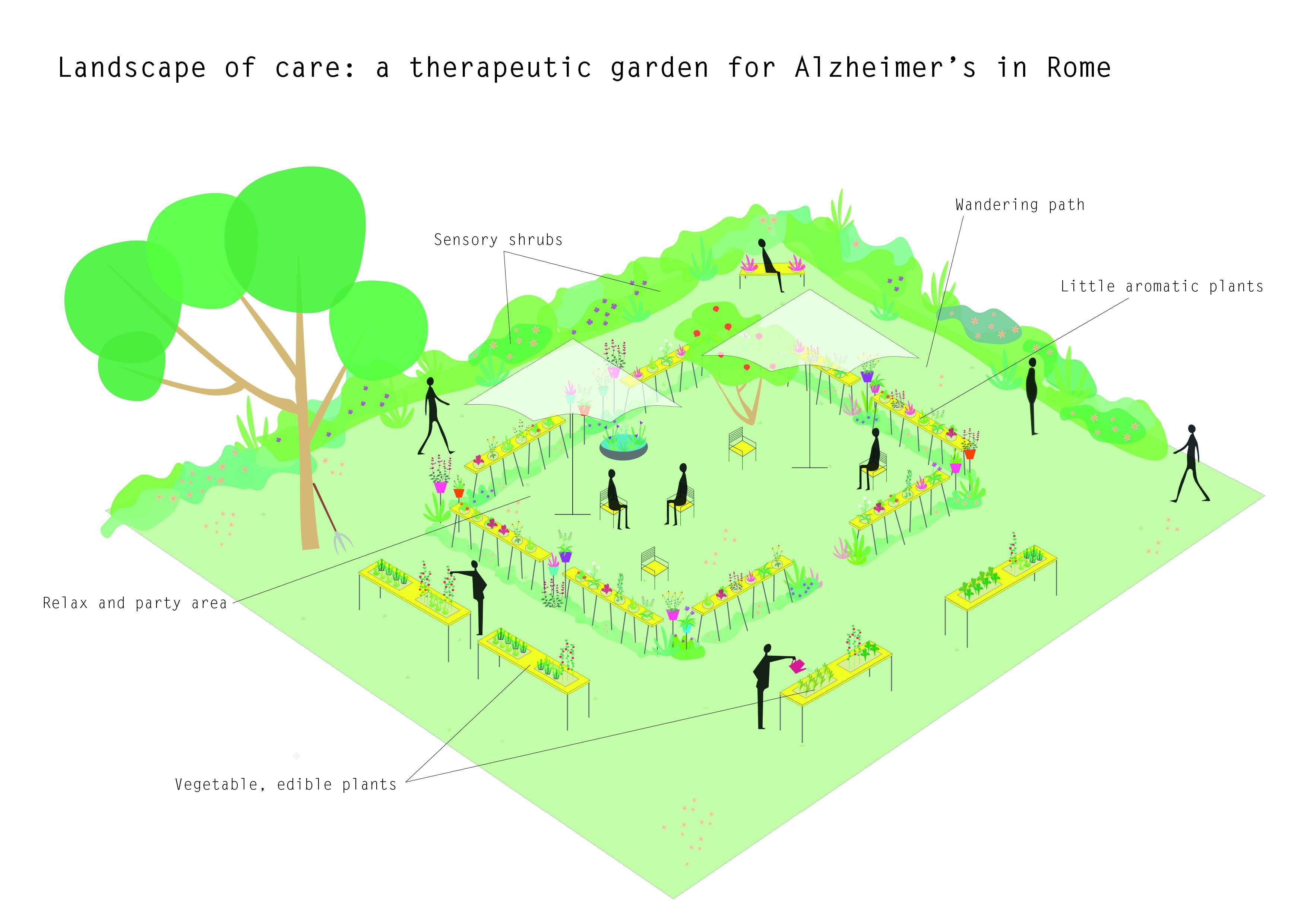

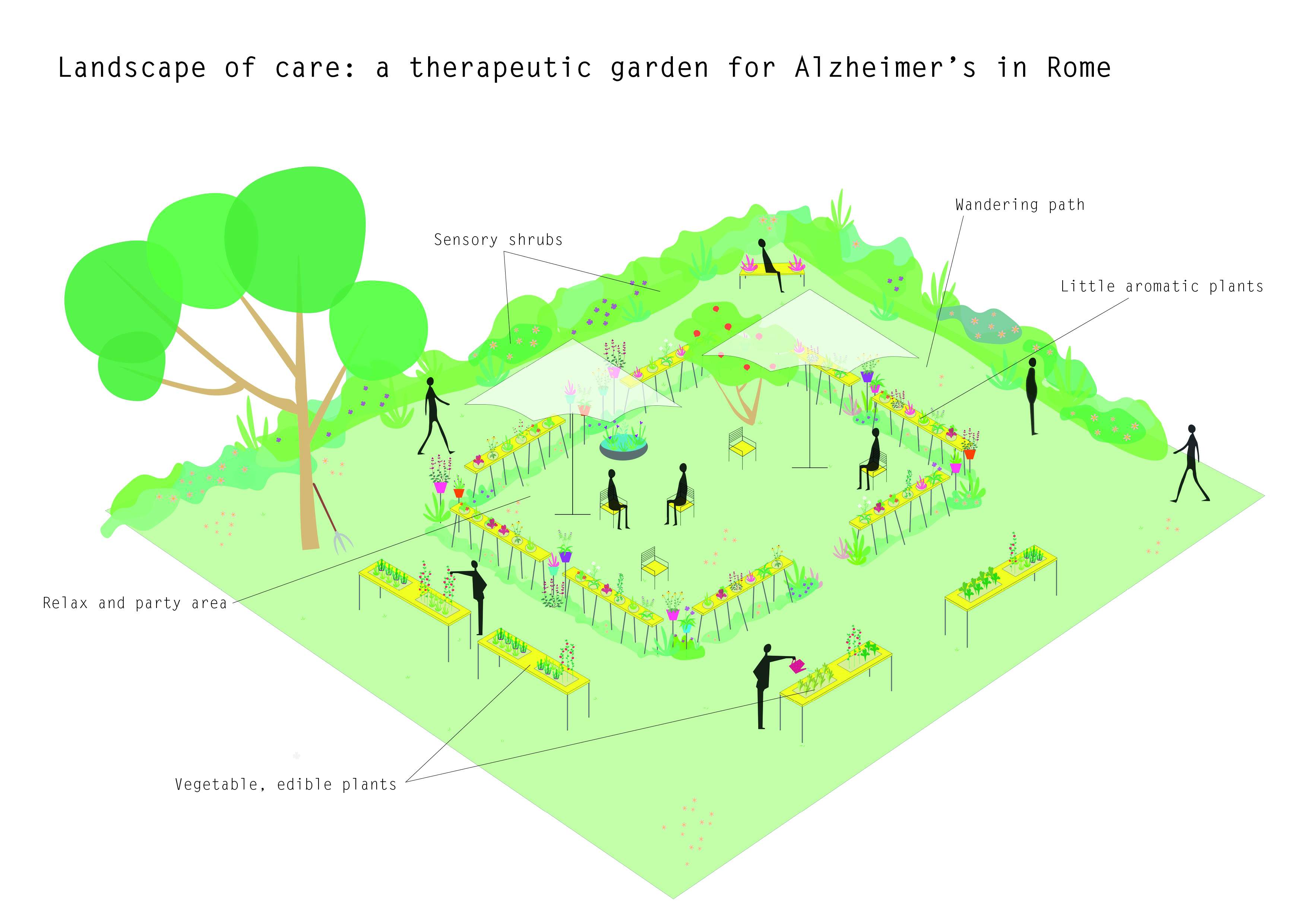

Description of the Project

-

The project is located on the outskirts of Rome, within the outdoor area of a day care center for people with Alzheimer’s disease.

-

Developed through a collaborative and inclusive process, the garden transforms a marginal space into a welcoming environment for care, interaction, and participation.

-

The design prioritizes accessibility and sensory stimulation, creating a multisensory landscape that engages sight, touch, smell, and memory.

-

A series of raised beds and large containers are placed at ergonomic height to allow easy access from a seated or standing position.These elements are arranged along a soft, meandering path that invites wandering and gentle exploration—supporting orientation, autonomy, and curiosity.

-

The perimeter of the garden is defined by dense, fragrant shrubs, which form a protective and immersive edge without enclosing the space rigidly.

-

The garden layout allows for both individual moments of quiet and opportunities for shared activity.

-

All plant species are edible, non-toxic, and chosen for their sensory qualities. The planting palette favors drought-resistant, low-maintenance varieties to ensure ecological sustainability and reduce water use.

-

The garden was built using reclaimed materials—wooden formwork panels and steel rods—selected for their simplicity, affordability, and adaptability.

Evaluation of the Finished Work

Therapeutic and Human Impact

-

The garden offers a dignified, a space where people with Alzheimer’s can reconnect with their senses, memories, and surroundings through simple yet meaningful actions.

-

Participants engaged in activities such as planting, touching the soil, and caring for plants, reinforcing a sense of agency and presence despite cognitive decline.

-

The space fosters emotional well-being, reduces anxiety, and provides comfort through seasonal rhythms, familiar scents, and tactile experiences.

Social and Participatory Impact

-

The project successfully involved people with Alzheimer’s not only as users but as co-creators of the space, through hands-on participation during both the construction and ongoing care of the garden.

-

Intergenerational and intercultural connections were fostered through inclusive workshops and collaborations with caregivers, volunteers, designers, and the local community.

-

The process helped create a shared, non-clinical environment where relationships are nurtured and everyday gestures become a collective form of care.

Environmental and Ecological Outcomes

-

The planting strategy encouraged biodiversity, with insect habitats and bird feeders integrated into the design to create a dynamic and living ecosystem.

-

Use of reclaimed and simple materials promoted sustainability and demonstrated that high-impact spaces can be created with modest resources.

-

The garden now functions as an informal educational space, sensitizing participants and visitors to ecological issues and sustainable practices.

Cultural and Spatial Significance

-

The garden reaffirms the role of landscape architecture as a tool for inclusion, regeneration, and democratic participation.

-

It challenges conventional models of care by offering an alternative rooted in proximity, presence, and embodied attention.

-

The project transforms fragility from a condition to be managed into a shared human experience, spatially expressed through design that supports choice, interaction, and beauty.

The creation of the garden for the Alzheimer day center in Rome contributes to Goal 3 of the 2030 Agenda by promoting physical and mental well-being through therapeutic contact with nature, while also addressing Goals 10 and 11 by fostering social inclusion of vulnerable groups and reimagining urban spaces as accessible, sustainable, and community-oriented environments.

With its ongoing commitment to social and ecological transformation, Linaria presents a garden specifically designed for people with Alzheimer. Conceived as an accessible, shared, and multisensory space, the garden responds deeply and symbolically to the needs of those affected by dementia. Unlike standardized institutional settings, it offers a living, evolving environment that stimulates sensory memory, gently reorients in space and time, and enables experiences of beauty, creativity, and participation. It becomes a place where fragility can be inhabited without shame—where even simple gestures like touching the soil, observing the seasons, or caring for plants become meaningful and empowering.

Developed with and for people with Alzheimer’s, and rooted in an urban context in Rome open to the wider community, Linaria’s garden is not only a therapeutic space—it is a laboratory of coexistence, where caregivers, families, volunteers, designers, children, and local residents come together. It transcends a logic of assistance, embodying instead a practice of shared, everyday care. It becomes a common good—a place where care is no longer delegated, but collectively cultivated.

Linaria’s approach is deeply ecological: it integrates health and well-being within a living ecosystem, celebrates biodiversity, and promotes sustainability through simplicity, reuse, and hands-on practices. In this way, the garden becomes a space of resistance and regeneration.

More than a therapeutic environment, the Linaria garden invites people with dementia to act, explore, remember, and care. In a time when Alzheimer’s often leads to a retreat from language, citizenship, and social life, the garden restores a right to presence and connection. It overturns the passivity imposed by illness and reactivates agency through the body, gestures, and relationship with nature. Designing from this perspective means recognizing vulnerability not as a flaw to be concealed, but as a fundamental and universally shared aspect of the human condition. Linaria envisions care as a spatial form—one that sustains relationships, offers orientation and comfort, but also freedom, agency, and choice. The garden values the non-verbal, fosters proximity, and supports inclusive, interdependent forms of coexistence.

In theoretical terms, the Linaria project represents a concrete application of “caring with”—in Joan Tronto’s sense—based on shared responsibility, embodied attention, and radical interdependence. Landscape here is not only therapeutic or aesthetic, but a daily act that creates bonds, preserves memory, and generates possibility—even where language fades.

To design gardens for people with dementia is to affirm the spatial value of care: to shape places that hold fragility while enabling action and dignity. Linaria’s garden reflects a commitment to justice and sustainability, restoring significance to every phase of life. At a time of dwindling public infrastructure and increasingly invisible or outsourced care, this project offers a tangible path to repair social, ecological, and health-related fractures.

Investing in such a space means more than improving the lives of those living with neurodegeneration—it means imagining a different kind of society, one that values fragility as a shared human reality and recognizes care as a radical act of transformation, connection, and hope.

Botanical Approach

Plants are at the heart of Linaria’s project, shaping a multisensory landscape designed to engage all five senses. The planting scheme emphasizes fragrance, texture, and color—creating a “garden of the senses” that evolves throughout the year. The selection includes species with contrasting leaf textures—smooth, velvety, leathery, or soft—such as sage, lavender, and pelargonium, offering both visual and tactile stimulation. Seasonal interest is ensured through a thoughtful mix of evergreen and deciduous shrubs and herbaceous perennials, allowing for continuous blooms and changes across the seasons.

The larger sensory shrubs are planted along the perimeter of the garden, creating a soft, immersive boundary. In contrast, smaller aromatic plants and edible species are placed in raised beds and containers at a comfortable height, making them easy to cultivate, touch, and smell—supporting accessibility and direct engagement.

Fragrant plants are carefully chosen for their intensity and quality, and positioned where their scents can be best appreciated. Yet, beyond flowers and aromatic leaves, the garden also embraces the natural smells of damp soil, cut grass, resin, moss, and stagnant water—evoking deep, instinctive memories.

The botanical choices aim to reduce water waste and favor resilient, low-maintenance species—highlighting not just the aesthetic and sensory value of plants, but also their ecological and environmental significance. The design embraces an informal, slightly wild character, inspiring the creation of gardens that are both spontaneous and sustainable.

To complete the ecosystem, workshop activities include the creation of insect hotels and bird feeders, placed in sheltered areas to encourage biodiversity and offer moments of quiet observation.

Participatory activities and seasonal engagement

At the core of the project are diy workshops designed to actively involve people with Alzheimer, valuing their residual abilities and transforming them into creative and meaningful actions. Each activity is designed not as therapy, but as an opportunity to reclaim agency through doing—celebrating the knowledge, gestures, and creativity that remain, and rooting them in a shared, sensory-rich landscape.

Simple yet engaging tasks—such as making seed bombs, propagating plants, and preparing aromatic salts with herbs from the garden—stimulate memory, coordination, and sensory pleasure. Participants have also created kokedama (moss balls), contributing to the garden’s aesthetic and tactile richness. In winter, the program includes the creation of small feeding devices for birds, allowing people to care for other living beings even when planting slows down. The project also took part in a call for a yarn bombing installation, drawing on the knitting skills of participants and transforming traditional crafts into public, collective artworks.

Construction process and inclusion

The construction of the garden reflects the values of simplicity, participation, and inclusion that guide the entire project. The structures were built using humble, repurposed materials—such as wooden formwork panels and steel rods—chosen for their accessibility, affordability, and adaptability to creative reuse.

Whenever possible, the work was carried out in collaboration with the people attending the Alzheimer day center, who were involved in hands-on activities such as preparing planting containers, filling raised beds, arranging elements, and observing the transformation of the space. Their contribution made the garden not just a place designed for them, but truly by and with them.

The assembly and construction phases were also part of a social inclusion initiative, engaging a refugee and a homeless person in a paid work experience that fostered dignity, learning, and a sense of belonging. The result is a garden that embodies not only care and creativity, but also solidarity and shared responsibility, making space for multiple forms of fragility and resilience to coexist and flourish together.

Presented for the Rosa Barba International Landscape Prize, this project reaffirms the political role of landscape architecture as a tool for social repair, ecological awareness, and democratic participation. It invites us to imagine gardens not as retreats from reality, but as active, generative infrastructures—where people, plants, and places can all find space to belong, transform, and bloom within an inclusive, multispecies city.